10 Best Films You Didn’t Know Were Based on Shakespeare

Shakespeare lends himself well to the medium of cinema. From epic, historical tales of war and conquest to fever dreams rooted in the outright fantastical, his plays beg for adaptation and reinvention in a visual medium—grounded by compelling stories and complex, believable characters. Here, we take a look at ten films you might not know were based on Shakespeare’s plays, as well as an examination of the Bard’s continuing legacy of influencing stories on the silver screen…

#1 Forbidden Planet (1956)

A pioneering science fiction film, Forbidden Planet plays as a loose adaptation of The Tempest, substituting Prospero for marooned scientist Doctor Morbius, his daughter Miranda for the Doctor’s own daughter Altaria and his enslaved sprite Ariel as science fiction fan fave “Robby The Robot”. Forbidden Planet plays beautifully as a relic of the Atomic Age—science (and with it, the threat of nuclear destruction) stands in for the magics of Prospero, as warns against the potentially destructive nature of mankind when power and ambition are allowed to run rampant in a ‘godless’, distant setting.

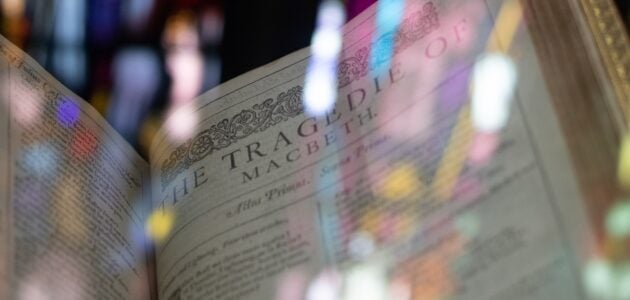

#2 Throne of Blood (1957)

The first of two films on this list by Japanese master Akira Kurosawa, Throne Of Blood plays out the drama of Macbeth in Feudal Japan. Kurosawa had long planned to adapt the work (which proved difficult during WWII due to its non-Japanese subject matter), and actually delayed the project for nearly a decade after learning about Orson Welles’ direct adaptation in 1948. Throne Of Blood draws on traditional Noh theatre elements; by modifying certain elements of Shakespeare’s text (such as swapping out the witches for an evil spirit), Kurosawa creates a story that feels grounded in the culture and history of Japan, while still speaking to the most engaging elements of the original text.

#3 West Side Story (1961)

While few might fail to make the connection between this classic tale of star-cross’d lovers and Shakespeare’s Romeo And Juliet, it is worth examining how this film touches upon new themes and, by the transparency of its own adaptation, helps us understand the original text all the more. West Side Story updates the Montague/Capulet tensions of the original plays by touching upon the very real race relations of the 1950s and 1960s: first- and second-generation immigrants of Puerto Rican and Polish descent. And for those who might have known the original play’s plot and saw the ending coming: remember that Shakespeare’s tragedy speaks of Romeo and Juliet’s doomed love right as the piece begins. His audience knew the story that was about to unfold, just as audiences of West Side Story knew it from the original text. This only goes to highlight the futility of racial hatred and violence.

#4 Chimes At Midnight (1965)

As with most films by Orson Welles, Chimes At Midnight was a nightmare to produce, dismissed by most critics upon release and now hailed as some of his best work. In Chimes, Welles adapted the story of Falstaff, drawing story and text from Henry IV (parts 1 and 2), Richard II, Henry V and The Merry Wives Of Windsor. Its cinematography has long been praised; Welles’ filming of the Battle Of Shrewsbury has been read as a staunchly anti-war sentiment, and is counted as an influence on the likes of such chaotic battle scenes as the opening of Saving Private Ryan. As with all Wellesian projects, it remains mired in the circumstances of its making. Look past this for some truly groundbreaking cinema.

#5 Ran (1985)

The second Kurosawa film on this list, Ran adapts the story of King Lear, with similar changes made to the text a la Throne Of Blood to reflect Feudal Japanese culture (Lear’s daughters, for instance, are gender-swapped to sons). Ran is the last of Kurosawa’s ‘epic films’; it is regarded by many critics as his final masterpiece. What is perhaps most interesting about Ran is how its protagonist, Hidetora Ichimonji, has been compared to the director of the film in which he features. Kurosawa has even made the comparison himself—likely meditating on the end of his life and career and the legacy he would leave behind. Ran features spectacular battles and favours wide shots over close-ups for an experience that feels simultaneously theatrical and cinematic. An utterly perfect film.

#6 My Own Private Idaho (1991)

In contrast to the other films on this list concerning the “Henriad”, Gus Van Sant’s stunning contribution to New Queer Cinema places the story of Henry IV and V in a world of street hustlers. Friends Mike and Scott (played to perfection by River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves) live a life of prostitution, partying and toying with Falstaf/father figure Bob. Searching for Mike’s absent mother, the two deal with the impending responsibility of adulthood by way of Scott inheriting his father’s riches. My Own Private Idaho is a dreamy, surreal experience (perhaps mirroring Mike’s own struggles with narcolepsy) that contrasts its stylised pseudo-Shakespearean script against an improvised, verite shooting style.

#7 The Lion King (1994)

You probably knew this one already. The Lion King is the most famous adaptation of Hamlet ever committed to celluloid; while there are some deviations from the text (the absence of the players subplot, downplaying the Prince’s faux-madness, the talking animals) it explores the dynamics of the original characters with a sophistication and clarity seldom seen in Shakespearean adaptations. Interestingly, Disney continued their Shakespearean adaptations with The Lion King 2: Simba’s Pride (Romeo and Juliet), and some have compared the breakout characters Timon and Pumbaa to that of Hamlet’s friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. We’ll conclude this passage with the information that Timon and Pumbaa’s canonical surnames are Berkowitz and Smith. Don’t say we never give you anything.

#8 10 Things I Hate About You (1999)

10 Things…’ status as an adaptation of Taming Of The Shrew is fairly well signposted by its recycling of character names its setting in Padua High School. It remains a popular text for study in high schools due to the easy parallels one can draw between film and play. If you’ve never encountered it, or remember it with disdain from having to study it in an English class, it is well worth a revisit. Strong performances help ground the sometimes-convoluted plot, and it engages satisfyingly with a feminist reading of Katherine that is (depending on who you ask) lacking in the original text.

#9 She’s The Man (2006)

Perhaps a stretch to include on any list of films beginning with the word “best”, this 2006 adaptation of Twelfth Night swaps out Shakespeare’s exotic Illyria for a high school, and riffs on the disguising of protagonist Viola as a boy so she can pursue her interest in soccer. Depending on who you ask, it’s either a surprisingly enjoyable comedy or a weak attempt to recapture the magic of 10 Things I Hate About You. Bet on the former camp having grown up watching it.

#10 The King (2019)

David Michod’s re-imagining of Henry IV and V is simultaneously beautiful and ugly: a film that uses stunning cinematography to capture a story grounded in the grit and dirt and blood of its Medieval setting. Despite the realism, however, there is something very post-modern in how the ‘epic’ of the story is so gloriously downplayed. Most of the dialogue is delivered in mumbles and whispers—the battles as slow and awkward as the pace of the film. Every facet of The King is crafted to perfection, and yet it never once engages in sensationalism. The result is an intriguing enigma.

Conclusion: Tenuous and Obscure Shakespeare

These ten films have been tied directly to Shakespeare—either as (loose) adaptations, or having taken enough influence from his work that the connection is undeniable to artist and audience alike. However, if we were to draw our net even slightly wider across the medium, we can see the way in which Shakespeare’s stories and characters appear in countless other films. Macbeth, the story of the underdog taking over only to be killed themselves leads us neatly to Scarface, just as Henry IV’s quiet, reluctant path to brilliant (if ruthless) ruler echoes throughout The Godfather. In the character of Lady Macbeth, we find the femme fatale. In Hamlet’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: the comic relief best friends such as Timon Berkowitz and Pumbaa Smith. The more you search for Shakespeare in film, the more you’ll find him. And why? Because his stories and characters continue to resonate. They signify good stories and characters—even when they’re clearly not. Is Game Of Thrones a loose adaptation of The War Of The Roses, its families squabbling for power for hours of drama at a time in a Medieval landscape? No. But its creators wouldn’t mind you drawing your own comparison…

Leave a Reply