Stoicism (Stoic Philosophy) For Actors

We are in the midst of an incredibly challenging, scary and turbulent time. The COVID-19 pandemic has completely changed the world forever and we are still not through the worst of it—even sixteen months after its onset. Even as I sit here writing this article now, Sydney (where I live) has gone into partial lockdown, impacting thousands of people, including the majority of people in my community: actors and artists like myself. Just as we were gradually gearing up for ‘new-normality’ again, now we find that our work prospects and upcoming shows and projects are once again at risk of not going ahead. And to add insult to injury, my laptop decided to delete my first draft of this article which was almost finished, forcing me to start from scratch today. Oh, the Humanity! (Okay, so that last point is the least of all these trials and tribulations we face at the moment.) What’s more, as residents of Australia, we have been relatively unscathed by the pandemic in comparison to the rest of the world. However, actors and artists in particular are having a truly rough time as the industry adapts rapidly to the new world.

Many of my friends are experiencing feelings of isolation, financial insecurity, a lack of purpose and all the mental health impacts that come with those factors. I, personally, have had a mixture of experiences in the past year and a bit, from a chapter of peace and resignation (knowing that the pursuit of acting work was a near-impossibility in lockdown) through to depression, isolation, a lack of motivation and a total loss of purpose and direction. “Turbulent” is an understatement.

One thing which has been my liferaft for me has been my curiosity and investment in learning about and practising the philosophy, ethics and practices of Stoicism. In this ancient philosophy, I have found incredibly relevant and practical tools for weathering the storms of life. I have recently begun sharing some of the things I’ve come across which come from Stoicism with actor friends of mine, and I’ve received a lot of feedback about how mind-blowing and useful it has been for them. I didn’t realise these practises would resonate with my friends so much, particularly actors, who are inundated with mindfulness practises and eccentric spiritual systems on a day to day basis. So, in receiving this feedback, I decided to attempt to share some of the wisdom I’ve come across in the last few months here, on StageMilk, with you!

In this article I’ll cover a brief overview of Stoicism – what it is and where it came from, but I’ll be focusing mainly on the invaluable insights which I think actors in particular could benefit from hearing and considering right now.

Just a lil disclaimer: I’m not a graduate of a philosophy degree. I’m really not a whiz kid when it comes to the historical origins of Stoicism, but I do feel I am able to offer some insights as to how Stoicism may be useful for actors—particularly in times like these. My primary reference for the history and insights of philosophy come from Ryan Holiday, author and creator of The Daily Stoic.

What is Stoicism?

Let’s start by identifying what it’s not. The word ‘Stoicism’ has become misrepresented over time. For many people, the word is synonymous with ‘emotionless’ or ‘unfeeling’. This is not necessarily the case. Holiday offers us a more accurate and concise definition:

“It’s a philosophy designed to make us more resilient, happier, more virtuous and more wise–and as a result, better people, better parents and better professionals.” — Ryan Holiday, The Daily Stoic

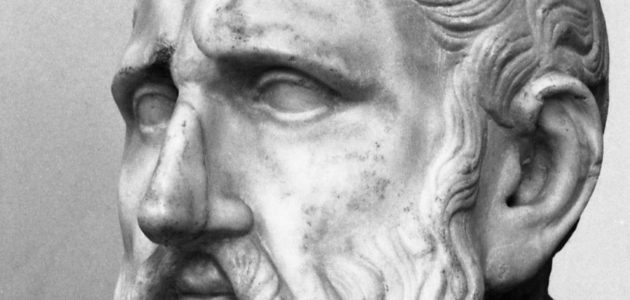

The word Stoic refers to the Greek Stoa Poikile, meaning ‘painted porch’. This porch was erected in the 5th century BC and was where the philosophy originated in the discussions between a merchant named Zeno and his followers. Many philosophers and practitioners of what later became known as Stoicism came after Zeno, but the main figures we refer to are Marcus Aurelius, the Roman Emperor; playwright and political advisor Seneca and Epictetus, a slave who went on to become a prominent teacher. These people lived at different times, but one thing they all shared was an experience and understanding of adversity, suffering, turmoil and conflict. Whether it was war, plague, slavery, exile or fear, these three lived through the worst of it and were able to process their experiences and live well in spite of them.

Why Stoicism?

The challenges we face today are not trivial. As I write now, we are thirty-four minutes away from the whole of the greater Sydney area going into a two-week lockdown (an announcement which has come in the time I’ve been writing). Many people have lost their jobs, livelihoods, family members, health and lives due to this pandemic. And many people face other unimaginable challenges on a day to day basis. As actors, our careers and industry are in disarray, and suddenly our futures seem scary and uncertain. The point of stoicism is not to diminish the seriousness of these challenges. It does not seek to trivialise. Instead, it seeks to teach us that suffering and adversity is a certainty in life, and we have the opportunity to learn to live in spite of that adversity, or be crushed beneath its weight.

A word we hear getting thrown around describing what an actor needs to be is resilient. We must bear constant rejection. We must withstand periods of uncertainty. We must look after ourselves after countless disappointments, and continue striving forward in spite of them. This word, resilience is at the heart of Stoicism. It is one of the key results of practising the methodology of stoicism, and this is why I feel it is essential to share with actors.

There are many many MANY components of the philosophy which I could not even begin to cover in this article. Instead what I intend to do is to cherry pick some of the core practices and ways of thinking which we, as actors, can start to adopt today: to better ride the waves of this pandemic, but also to increase our resilience in our careers. Let’s begin by talking about some aspects of the stoic mindset, and then we’ll move on to some practical aspects of the philosophy we can start for ourselves.

The Stoic Actor’s Mindset

Come and have a seat next to me on this virtual StageMilk porch and let’s talk about Philosophy. The sun is setting, we’re drinking our favourite warm beverages, and we’re not worried about COVID-19 right now because we’re sitting and chatting. Allow me to wear the mantle of the Stoics and wax lyrical about some of their core mindsets—why they are relevant to us today and essential for us to adopt.

1. “You become what you give your attention to… If you yourself don’t choose what thoughts and images you expose yourself to, someone else will.” — Epictetus

You may be clear about your goals, dreams and ambitions. You may know what you wish to achieve in your career as an actor. But how much consideration have you given to deciding who the person is you wish to become? Both in our careers as actors and as humans riding the waves of uncertainty. This message from Epictetus can be of great value.

We are assaulted by a barrage of news, information and opinion on a daily basis. We know well of the power this onslaught possesses in shaping our beliefs and actions. This same power is held by our thoughts, self talk, and what we pay attention to. If we submerge ourselves in the doom and gloom of the world, all we will continue to see is doom and gloom. The same goes for our sense of potential and self belief. If all we pay attention to are our losses and perceived failures, we will grow to become those failures. If we tell ourselves we’re not good enough, we won’t be.

“Our life is what our thoughts make it.” — Marcus Aurelius.

As actors, there are plenty of opportunities to find doubt in our potential. I am constantly battling it. In fact, I’d say that the question of my own potential is one of my biggest hurdles to overcome. I am constantly fighting the belief that I am not good enough to be successful as an actor. An alarming truth we learn from Stoicism is that this fear, this imagined measurement of my capacity WILL become my reality unless I seek to actively change it. And to actively change it, I must shift where I place my attention. If you begin to search for the beauty of the world, you will soon begin to find it, even though it may be surrounded by doom and gloom. If you wish to believe in yourself more and in your potential, you must pay attention to the evidence which supports the fact that you do have potential. This evidence can be small, too; booking an acting job isn’t the only source of validation in this industry. I find the evidence when I practise for the sake of practising. I find evidence when I watch a really good movie and am moved to tears. I find evidence when I feel like I did effective preparation which allowed me to do a good job. I find the evidence when I have something to say in a rehearsal room about a story or a character. I find evidence when I form opinions about a play I’ve just seen. If I give my attention to all this evidence, gradually I will begin to notice my self-perception shifting: from an actor with minimal potential to one with great prospects and an exciting future.

So ask yourself this question: who do I want to become? Once you’ve identified this, what do you need to give your attention to (or take it away from) to move towards this ideal version of yourself?

2. “You cannot learn that which you think you already know” — Epictetus

It seems to me that, as actors, we must tread a fine line between knowing and not knowing. We must know enough about our craft and capabilities to be able to function effectively on set, in the theatre or any performative environment, but we must also be constantly prepared to not know. We must remain curious in this profession to continue to progress. Performance requires a level of empathy and vulnerability which is hard to manifest from a fixed mindset. Epictetus puts it clearly for us in the above phrase, telling us quite simply that if we think we know something, we are no longer in a place where we can continue to learn.

I find myself treading this line quite often: oscillating between periods of confidence and doubt in my ability. It seems to me that instead of trying to lean into either end of the spectrum of confidence and doubt, what is required from me is endless curiosity and finding peace with not knowing. When I allow myself to not know, there is always more work to be done. A character or story, by that logic, will never dry up or become dull, because there will always be more to investigate. A friend of mine put it to me in an interesting way in conversation the other day. They said, “When you feel that you know all there is to know, turn your attention instead to discovering what you don’t know you don’t know.” Head hurting right now? Same. But the sentiment of both this phrase and that of Epictetus is that we must find comfort in not knowing and allow our curiosity to propel us forward.

3. “We don’t abandon our pursuits because we despair of ever perfecting them.” — Epictetus

Choose progress over perfection. Finding peace with not knowing lends itself very well to this principle. Acting is a craft and an art, after all. Striving for perfection is not only limiting but it is impossible. Can we say the greatest actors and artists of our time have reached a place of perfection? I’d say no. The greats are great because they place their focus in progress over perfection. They are constantly striving to take one step forward, to get just a little bit better.

This principle can be liberating for actors to adopt. The goal moves from ‘being the best’ to continually getting better—a far more attainable dream. To ‘be the best’ is a flawed pursuit. How can we measure it? By whose metric are we the best? And what do we gain from learning that we have become the best? Where do we go from there? Each day we strive to be the best is a day in which we fail. Every day we work towards becoming just a little bit better is a day in which we succeed.

4. Take Responsibility For Your Life

We wouldn’t have to look very far to find things to complain about right now. And what’s more, we’d find it a simple task to identify those at fault for the situations which challenge us. It could be the politicians, the casting director who didn’t give us the job, the Uber driver who took a wrong turn and made us late, the guy who went out without a mask after a positive COVID test. Complaint and blame are super easy things for us to access, but the Stoics tell us to avoid these things at all costs. Instead, they teach us to take full responsibility for our lives and what is within our control.

“But complaining is so comforting precisely because it excuses us from taking responsibility for our own thoughts and actions.” — Stephen Hanselman, The Daily Stoic

Sam Harris, creator of the Waking Up meditation platform, often says the phrase “Live an examined life”. I love this phrase, and I think it is very Stoic in nature. It is our duty to examine our lives and assess why we are where we are. It is so much easier for us to find the cause of our situation in the fault and actions of others, and whilst this may give us temporary relief from dealing with our problems, it is merely avoidance that will see us prolonging our suffering.

We should strive to constantly be in a place of self examination, asking ourselves the important questions about the choices we have made which have landed us in this position. Marcus Aurelius states, “You get what you deserve. Instead of being a good person today, you choose instead to become one tomorrow.” — Meditations, 8.22.

Questions we are able to ask ourselves include: “What were the choices I made which landed me here?”, “What do I need to do to move past this?” and “What can I learn from this?”.

Perhaps the most well known sentiment of The Stoics was made famous in the film Dead Poets Society, starring Robin Williams, the teacher who told his students ‘Carpe Diem; seize the day’. We have the opportunity today to take responsibility for the position we are in in our lives. Once we take that responsibility we then may take the steps towards changing it.

This principle becomes the most challenging in times of tragedy and unavoidable challenge. How can we possibly strive to take complete responsibility when a family member is sick? How can we reserve blame when someone is clearly at fault? Once again, these principles do not seek to trivialise. The Stoics themselves needed to develop ways to live in spite of tragedy and adversity. This principle aims to teach us that nothing will be gained by complaining, blaming, or avoiding taking responsibility, even in the worst of times. Those devastating times may make this task infinitely more challenging, but suffering may be reduced by reserving our focus and attention for our own actions and choices, rather than the actions of others.

“Sister, there are people who went to sleep all over the world last night, poor and rich and white and black, but they will never wake again. Sister, those who expected to rise did not, their beds became their cooling boards, and their blankets became their winding sheets. And those dead folks would give anything, anything at all for just five minutes of this weather or ten minutes of that plowing that person was grumbling about. So you watch yourself about complaining, Sister. What you’re supposed to do when you don’t like a thing is change it. If you can’t change it, change the way you think about it. Don’t complain.” — Maya Angelou, Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now

5. “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.” — Marcus Aurelius

Stoicism, like many schools of philosophy, emphasises the importance of regular contemplation of our own mortality. The phrase used by the Stoics is Memento Mori. This phrase translates as: “Remember you must die.”

This sudden lapse into morbidity may have some of you feeling a bit deterred, which I absolutely understand. This is one aspect of Stoicism which I find particularly difficult to actually practise. It is terrifying to contemplate our own mortality, but the Stoics urge us to do this for the clarity of life it may provide to us. Feeling that this practise is morbid and depressing is to miss the point of the practise. Seneca writes, “Let us prepare our minds as if we’d come to the very end of life. Let us postpone nothing.” Like Carpe Diem, this principle reminds us to take the action we wish to take today, to stop living our lives for tomorrow.

As an actor, I have spent years of my life delaying important actions, for fear of missing out on things that may happen in that time. Let me be more deliberate: I want to live overseas. This is an experience I’ve never had before and it is something I feel will enlighten me, and remind me of how beautiful the world is and how small I am within it, (another liberating reminder from the Stoics). I have lived in Australia my entire life, and I have never left because I’ve always worried that something will come up whilst I am away. Moving overseas has always been something that will be better for me to do next year. What this pandemic has taught me is that next year I might not have the option. Tomorrow I may not have the option. Memento Mori: remember that I must die. I may not wake up tomorrow morning. I need to take action today on the things that are most important to me, and I think you should do the same.

6. “It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it.” — Seneca

We’re still on the morbid train, here, for another moment or two. My apologies! Seneca, in his text, On the Shortness of Life, enlightens us by disputing the commonly thrown around phrase, “life is too short”. When tragedy strikes, then of course this is the case. Time has been robbed from us where it should have lasted longer. But what is considered less is the idea that there is plenty of time to live a full and worthwhile life, we just squander away our time carelessly because we do not understand the true value of it.

“People are frugal guarding their personal property; but as soon as it comes to squandering time they are most wasteful of the one thing in which it is right to be stingy” ― Seneca, On The Shortness of Life.

Take control of how you spend your time. Keep that word, spend at the forefront of your mind. Time is the most valuable currency you have, so spend it wisely. Well spent time fills a well-lived life. Wasted time is the real tragedy of our lives. I know this is an area I need to focus on more. How much time do I squander on things which are not important to me, like social media or worrying about what other people think of me? How can I be better using my time to move towards the person I wish to become?

7. Amor Fati: Love Your Fate

We’ve spoken already about the resilience which is required from actors. We are told, “Not this time” over and over again by the opportunities which we’d give a limb to be a part of. The Stoics take this resilience one step further with the principle of Amor Fati; they tell us not only to bear our fate, but to love it. So, I didn’t get that role in The Lord of the Rings which I’ve been dreaming about for most of my life? Ok. Amor Fati. I love my fate. I love the life I will lead and the things I will experience in spite of that loss.

When I am not in the best headspace, I will sometimes reflect on a decision I needed to make early on in my career between an acting job I had already booked and another job I was in the running for. The job I was in the running for was a dream job full of shiny exciting experiences. The job I had offered me security and certainty, and I had already signed up for it. I decided to do the job I had, rather than pursue the dreamy job and risk tarnishing my reputation. In times of no acting work since then, I have wondered what would’ve happened had I made the other choice. This wondering has caused pain and feelings of regret, but with that pain comes guilt. By regretting that decision, I regret all the experiences I’ve had since then, the things I’ve learnt, the friendships I’ve formed and the memories I’ve shared. To regret is the tragedy. To love my fate is to find an end to my suffering. Amor Fati reminds me to love everything which is in front of me and has led me to this moment, and allows me to continue moving forward with ease, rather than dragging a burden of regret or guilt behind me.

Whilst researching this principle I came across an anecdote which articulates Amor Fati perfectly, and really moved me. I felt it was important to share it with you:

“As with any important lesson, it is best to learn, practice, and rehearse before you absolutely need it. Before it counts. When it counts is when you find out your infant son might have an illness that will debilitate him and ultimately kill him before he sees his twentieth birthday. Like I did. It is then when you have to… be reminded that you have a choice in how to perceive this event, and look in the mirror through tears and consider something: Maybe, just maybe, if he wasn’t sick I would have taken him for granted. Now I won’t. Now I’ll make every second count. I can choose to be grateful for twenty years fully-lived with my son versus sixty years mostly wasted.” — Brendan Hufford, The Daily Stoic

And hey … I didn’t get that job in The Lord of the Rings, but I still get to experience the story. I still get to love the books and the movies and be moved by them. Gandalf himself echoes the sentiment of Amor Fati, and it would be simply impossible for me to not include it in this article:

Frodo: I wish the ring had never come to me. I wish none of this had happened.

Gandalf: So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us. There are other forces at work in this world, Frodo, besides the will of evil. Bilbo was meant to find the Ring. In which case, you were also meant to have it. And that is an encouraging thought.

Thanks for indulging me. Let’s move on.

Habit and Practices of the Stoic Actor

The challenge of Stoicism is taking the theories and principles of the philosophy and practising them. We must actively incorporate these ideas in our lives to test the benefits they may have. Here are a few practical tools from Stoicism you might consider incorporating into your life.

1. Journaling

The Stoics did not invent the art of journaling, but they did believe in it and rely on it. In line with the phrase from Sam Harris, “Live an examined life”, journalling is one of the best and most accessible ways we can work towards knowing ourselves better. I have been journaling on-and-off for the past 4 years, and I can honestly say it has changed my life. The journal itself is a deeply precious document to me, and it contains a record of my thoughts from the past which I will often re-read with a smile as I reflect on how far I have come since I wrote those words. My journal is the place where I can speak totally honestly and without censor or judgement coming my way.

Many acting teachers and successful actors will praise therapy as an essential tool all actors must experience to come to know themselves, and in doing so they will become better at their craft. I really believe in this theory—in fact, I think therapy can be of value to everybody. Actors strive to understand and portray human beings, but how can they do that fully without understanding themselves? Therapy can help with this immensely. But, therapy can be prohibitively expensive which is a restrictive factor for many people. Journaling is a cost-free way to allow us to learn more about ourselves and untie some of the matted knots of our mind.

If you’d like to know more about journaling, why and how you should do it, head here: The Art of Journaling. I found this page really useful.

2. Temperance

The four virtues of Stoic Philosophy are the following: Courage, Justice, Temperance and Wisdom. These four virtues are the pillars on which the philosophy stands. Each of these four virtues deserves its own page in this article, but for the moment I just want to focus on the virtue of Temperance and how it relates to actors.

I, personally, want to be an actor for the rest of my life. This means I need to look after myself, and to look after myself I need both discipline and self restraint. The stoic virtue of Temperance relates to these points. Stoic examples of temperance, discipline and self restraint are many. A few of the most prominent examples are that of waking up early, establishing good consistent habits and practising gratitude.

Actors can benefit from each of these practises. Waking up early is an ongoing battle in my life. The snooze button is always more magnetic in the mornings, and I will continue to strive to develop discipline in this area. Because it’s essential! Actors are often robbed of structure and consistency, so we must generate it for ourselves. Marcus Aurelius himself struggled with this issue, and wrote down this advice for both us and himself:

“At dawn, when you have trouble getting out of bed, tell yourself: “I have to go to work — as a human being. What do I have to complain of, if I’m going to do what I was born for — the things I was brought into the world to do? Or is this what I was created for? To huddle under the blankets and stay warm?” — Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 5.1

Waking up early consistently is one of the many habits which the Stoics believed led to excellence, which was a primary aim of theirs. Habits themselves were the key. As Aristotle said, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” Again, actors are severely lacking in structure and consistency, so finding routine or habitual behaviour can be tricky. In line with striving for progress rather than perfection, what habits can we generate which will help us achieve our goals?

And finally, gratitude. The stoics believed that active gratitude for your life was essential for positive functioning, and a key to happiness.

“It is easy to praise providence for anything that may happen if you have two qualities: a complete view of what has actually happened in each instance, and a sense of gratitude.” — Epictetus

What a wonderful challenge for us, to take all the things in our lives and careers which trouble us and turn them into something we feel grateful for. How much better are we for waking up in the morning feeling thankful for being here than we are resentful of all that is around us.

These three practices: (1) waking up early, (2) forming good habits and (3) practicing gratitude, are all components of the Stoic virtue of temperance. Temperance, discipline and self control for actors can be a key component in the longevity of our careers, and is something we should all work towards and practise.

3. Premeditatio Malorum

The final tool of the Stoics I felt was worth sharing with you is called Premeditatio Malorum, or “the premeditation of evils”. As I’ve said, in the time it’s taken me to write this article from start to finish, my hometown has been plunged into a full-blown lockdown. My friends have had shows and work cancelled, and the security of my upcoming show (which was cancelled in 2020 due to COVID) is now under threat. The Stoics advise us to not allow ourselves to be caught off guard by what life throws at us. By living an examined life we are already halfway there, but what’s needed in addition is the contemplation of what might arise in the future and planning for that eventuality. For me, I need to (and will, today in fact) consider and plan for the possibility that the show I’m in won’t go ahead. Even though this pains me to even consider, I’m far better off for coming up with a bit of a contingency or at the very least a reminder that I will be ok even if the show is cancelled, rather than hoping everything will be fine and pretending there’s no risk to the situation at all. The Stoics believed that fear and hope were two sides of the same coin, both imagined projections of the future which take away from our investment in the present. Instead of hope or fear, I choose to take action today.

This exercise of anticipating the worst case scenario has been wonderfully summarised and transformed into an incredibly practical exercise by Tim Ferris, he calls it “Fear Setting” (rather than Goal Setting). Check it out!

Conclusion

I’m sure I’ve grossly oversimplified or bastardised the philosophy of Stoicism here, but I hope that in reading this article you have identified some things you can do, practise or incorporate into your mindset which will make you a better actor and more resilient in your life and careers.

We’ve spoken about some of the Stoic virtues:

- You become what you pay attention to,

- Learning is in opposition to knowing,

- Choose progress over perfection,

- Take responsibility rather than turn to blame or complaint,

- Memento Mori, and

- Amor Fati.

There’s quite a lot in that list, but it barely scratches the surface of the valuable insights of the Stoics. I’d encourage you to read more if this article has caught your interest. We also spoke of some practices of the Stoics; journalling, forming good habits, and preparing for all possibilities—even the ones which scare us.

The four pillars of Stoic virtue are Courage, Justice, Temperance and Wisdom. Even if we don’t align with Stoicism, surely we can all agree that these four concepts are worth striving towards, both as human beings generally but also as actors. Courage is essential in acting and any style of performance: we are constantly being asked to bear our souls and be vulnerable for an audience. We must understand justice, what’s right or wrong in this world, to be able to relate well to people but also to effectively understand the characters we seek to play. Temperance, we have already spoken of. We are what we repeatedly do. What are you doing every day? Does it reflect the person or type of person you wish to be? If not, why? Would you like to seek to change that? And finally: wisdom. Which of the great actors can we say is not wise? Wisdom is essential for actors. The wise actor is compelling to watch, as they possess an understanding of what it means to be human which is deeper than most. Striving to become wise surely must be a priority for all of us, whether we are an actor or not.

I hope you’ve enjoyed diving into the practices and philosophy of The Stoics. I know I have! For me, writing this has been a fantastic way for me to clarify how I feel about this way of thinking and try to articulate why and what about it has been essential for me over the last few years.

If you, too, are going through a tough time at the moment, whether you are affected by COVID or something else, I hope there’s something in this for you. Remember there are always those you can reach out to for help or to talk to if you need.

Take care! Carpe Diem!

For more about your acting career during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, check out our piece called Maintaing an Acting Career Post Pandemic.

Leave a Reply