How to Act Shakespeare

Acting Shakespeare, in many ways, is like acting any other style or genre. However, due to the complexity and intricacy of the text, it can require a more thorough investigation by the actor. It is almost another language, yet it cannot be performed as such; it must fall onto the ears of the audience with absolute clarity. There is no definitive guide on how to act Shakespeare, so as you read more about him, remember that your natural instincts are invaluable. There will be many people who tell you there is a right way, but it just isn’t the case. I have laid out a some personal tips and ideas that may help you on your way to better understanding and performing Shakespeare.

– Understand the Words

– Understanding the Verse

– Further Poetic Devices

– The Creative Work

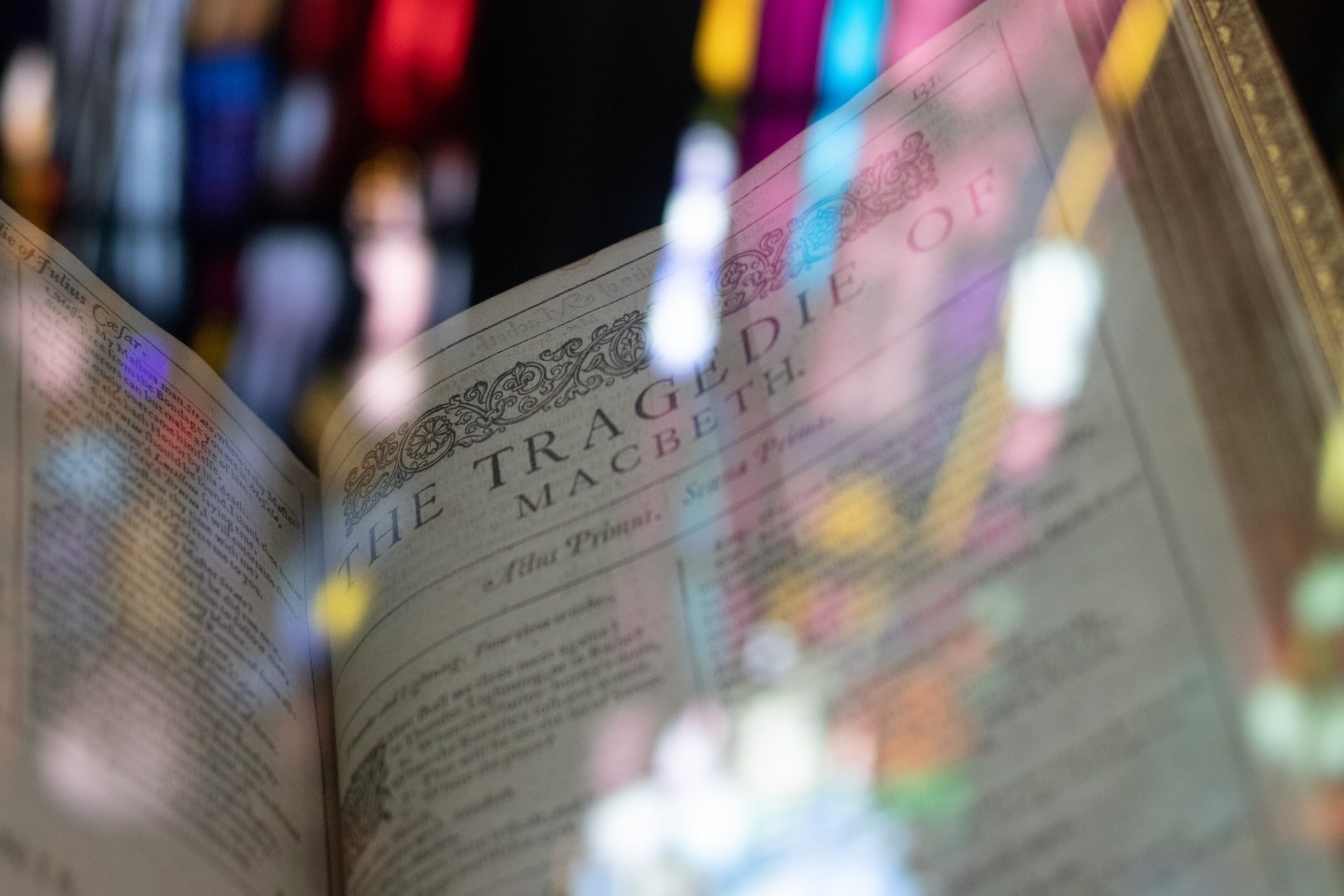

Understand the Words

Understand every word and phrase. If you encountered an unfamiliar word or phrase in a contemporary script, you’d most likely take the time to Google its meaning before moving on. And yet, for some reason, actors often think Shakespeare is too complicated or out of reach; therefore, they don’t bother to invest the time in understanding the words, delivering the text without clarity or meaning. Here then, I believe, is the greatest rule in how to act Shakespeare: if you don’t know what you’re saying, the audience doesn’t either. If they don’t understand what you’re saying, they aren’t engaged.

How to understand the words?

- The dictionary: this is your best friend when working on any Shakespearean text. A great resource is David Crystal’s Shakespeare Glossary which is a dictionary specific to Shakespearean language. A normal dictionary will have most definitions.

- No Fear Shakespeare and LitCharts are two great resources that are available for free online (and No Fear Shakespeare has a printed book version). They are basically Shakespeare’s plays translated into modern, easy-to-understand English. They are fantastic! There is no shame in using these.

- Annotations in the text. Many modern editions of Shakespeare plays will have annotations/footnotes directly on the page, or at least a glossary of terms at the back of the book to help you navigate what is being said. While you might feel inclined to skip over these on your first read, they are worth revisiting. In particular, the Arden editions of Shakespeare plays provide wonderful annotations and notes for performing Shakespeare.

Whenever you don’t understand a word or phrase, just remember to be honest with yourself. Don’t rely on context alone to carry you through: sometimes the particular word choice will carry a far greater significance that you might realise!

Understanding the Thoughts

As the words become clear, you will start to unlock the meaning of each line. Then, in turn, you will be able to unlock each thought: the ideas that drive the text as a whole. Simply put, a thought is a new idea. And you must understand every new idea for the text to come alive. Often, the punctuation is a great guide in helping you identify the thought: a full stop indicating the end of that particular thought. However, punctuation may vary between editions, therefore use your instinct as well as your understanding of the text to help you work out where the thoughts begin and end.

Tip: Each line isn’t necessarily a different thought. Thoughts can vary from one to twelve lines.

Tip: There is very little subtext in Shakespeare. What you say is what you mean. So it is vital you understand what you are saying and strive to be as clear as possible.

Paraphrase

Now that you understand every unfamiliar word and you have marked out the thought shifts, have a go at paraphrasing the text; put the text into your own words. This is common practice in rehearsals for Shakespeare plays and is great to do with audition monologues or scenes you are working on. If you can’t speak the monologue in modern English, you can’t truly communicate it in Shakespearean English.

Tell the story

Once you understand the thoughts, start broadening your perspective. Move on to the rest of the speech: what is it trying to say? Then look to understand the particular scene you are working on and how that scene fits in with the whole play. In Shakespeare, everything builds on what precedes it; understanding the story helps you tell your part more clearly.

Tip: When working on a soliloquy, look for where the character is using compare and contrast, question and answer or disagreement and agreement in the speech. In soliloquies, the character is usually debating what course of action he/she should take next, so try to figure out these changes in thought as this is what is interesting for the audience.

Tip: There will always be people in the audience who can’t understand you. Shakespeare is a two way street that requires an audience to be fully engaged and listening, but you owe it to those who are truly listening to share the words with clarity and meaning.

Read more Shakespeare

One of the best ways you can familiarise yourself with Shakespearean language is to read and watch as many of his plays as you can. Seek out filmed adaptations, and see any live productions in your area. This will help his words seem more natural to you. Every bit of Shakespeare you can experience will help make the next play you read clearer and therefore more enjoyable.

Tip: If you’re looking to get to know one of Shakespeare’s plays for its story and characters, don’t look past adaptations that don’t use his language. Check out our article on “Ten Films You Didn’t Know Were Based On Shakespeare” for recommendations as varied as sci-fi to Samurai to The Lion King!

Understanding the Verse

If you take the above steps to thoroughly understand the text, often the technical elements of Shakespeare’s language become much easier to tackle. A strong knowledge of aspects such as verse and meter can give you a serious edge when acting Shakespeare; teasing meaning out of his words, and how they fit together on the page.

Verse and Prose

Shakespeare uses three main types of text: blank verse, rhyming verse and prose. Blank verse is poetic language written in Iambic Pentameter, commonly used by high-status characters, in formal settings such as a royal court, or for intense emotion. Rhyming verse is another form of poetic language in which Shakespeare uses rhyme, often in rhyming couplets that signal the end of a scene or sonnet. And finally prose is every day, ordinary speech; it is typically spoken by lower status or humorous characters.

Examples of different forms of text:

Blank Verse

Hamlet speech

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew!

Rhyming Verse

End couplet of Sonnet 65

O, none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

Prose

Benedick (Much ado about Nothing)

This can be no trick: the conference was sadly borne; they have the truth of this from Hero. They seem to pity the lady: it seems her affections have their full bent.

Iambic Pentameter

Iambic Pentameter is the rhyming verse most associated with Shakespeare; while it can feel unnatural to speak in this manner when you first try acting his words, Shakespeare actually favoured this style of verse as it actually mimics natural human speech.

Iambic Pentameter consists of five rhythmic iambic feet per line. A foot is a rhythmic, poetic unit demarked by its number of syllables and how they are stressed. And an iambic foot is consists of an unstressed-stressed combination: da-DUM.

Here’s an example from Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

[Da – DUM Da – DUM Da – DUM Da – DUM Da – DUM] [My mistress with a monster is in love.]At times, Shakespeare does break away from Iambic Pentameter–particularly in his later plays, and especially if a character is in turmoil or in heated debate. Often, he will employ a type of foot called a trochee, which is the opposite of an iamb (DUM – Da).

Take a look at this famous line from Hamlet’s soliloquy:

[Da – DUM Da – DUM Da – DUM DUM- Da Da – DUM (Da)]

[To be, or not to be, that is the question.]

Notice how the stresses help you identify the important ideas in the line? How the most important notion, of the central question Hamlet is asking, is singled out with a trochee? Shakespeare uses breaks in the meter to stress things the actor (and, therefore the audience) needs to be aware of. Look for these like clues when you break down the script.

Tip: For more insight into mining Shakespeare’s text for meaning, take a look at our Decoding Shakespeare article.

Key Words

Even when a line of Shakespeare’s is written in perfect iambic pentameter, you can’t speak the line in this constant Da-DUM, Da Dum pattern. It would become monotonous and uninteresting to the listener. A useful rule is to highlight or ‘hit’ the final word of the line and as well as another key word within the line.

Here’s an example from King Lear, spoken by Edmund:

Thou nature art my goddess

nature: key word

goddess: end word

Edmund is talking about being a bastard child, saying that nature, to him, is more important than the rules of marriage. If you stress nature and goddess when speaking the line, it helps give it accurate sense. Use the meter to make sure the keyword isn’t on the unstressed syllable. Shakespeare wrote to help the actor, and his rhythm is a great guide. So use him. Often, the nouns or verbs are the sense of a line and, therefore, are the keyword. This rule can sometimes be broken and there may be more than one keyword, but usually only one is needed. The end word of each line is important because Shakespeare often places a lot of meaning there. Try saying the end word of every line in your monologue and often you can get the sense of it. This shows its importance and it can’t be dropped.

Tip: Nouns tell the story, verbs give the energy and adjectives give the vision.

Further Poetic Devices

Poetic and rhetorical devices such as these can be traced back to Ancient Greco-Roman plays and texts. As Shakespeare was a student of these, it is no wonder that they feature heavily in his own work. Here are a few key ones to remember as you read and perform Shakespeare’s works:

Assonance: This is the recurring use of vowel sounds (often called vowel rhyme) as in: no man knows.

Alliteration: This is the recurring use of consonants in a line or sentence: fancy free Fred.

Onomatopoeia: A word that sounds or feels like the word itself: boom. Many words invented by Shakespeare, such as “bubble” in Macbeth, began as onomatopoetic devices.

Puns and sexual jokes: There are a number of puns in Shakespeare’s text, many sexual. Shakespeare wrote marvellously for the both upper and lower classes so he used a lot of low brow humour as well as beautiful poetry. Often, as you find the meaning of words and thoughts the sexual connotations and puns are revealed.

Antithesis: This is a crucial component of speaking Shakespeare. Antithesis simply means opposition or contrast. Shakespeare juxtaposes one idea against another for poetical purposes, yet it also helps characters come to decisions and make strong arguments. It is also important for clarity and storytelling. ‘To be, or not to be, that is the question’ is in its self an antithetical line. Hamlet debates whether to live or to die: two very different choices.

The Creative Work

Imaging and targeting

You have to have strong, clear images for everything you say. It’s very easy with Shakespearean language to just float on it, never understanding what you’re actually saying. Every word has weight. Sometimes going through the text, word by word, playing with volume and range can be great. Other exercises like changing direction on each thought can help keep the text varied.

Acting work

Shakespeare’s text might be more complex than contemporary text, yet the acting fundamentals are the same. Firstly, don’t try to manufacture character. Character comes in what you do: your actions. Oberon (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) is a king, but that status comes in how he treats Puck and other characters and how other characters endow him. You can work physically on a role such as Oberon. A king would likely be proud and stand tall; his servant, Puck, perhaps quicker paced and flustered.

Accent

Unless it is has been otherwise specified, use your natural voice and accent. Don’t try to mimic RP (Received Pronunciation) thinking it’s the correct or better way of speaking Shakespeare. In fact, in Shakespeare’s time the accent would have been vastly different from RP; most scholars agree it would have sounded closer to a ‘Boston’ accent from the United States! Be proud using your natural voice.

Location

Location is another important factor that influences the scene and although more and more Shakespearean production are taken out of context and modernised be aware of the intended location of the scene: in a bedchamber, on a battlefield, or during a storm. It can often affect the energy and given circumstances of the scene.

Dynamic

Always look to find dynamic in the text. Don’t let it become a generalised wash. Where is it fast-paced and where does it slow down? Where does your character relish in what he/she is doing and when are they unperturbed? Be a detective. Constantly go back to your text and play with it. See what works best and interrogate why…

Conclusion

As I said at the start of this piece, the best thing you can do is to saturate yourself in Shakespeare. Try to listen to great Shakespearean actors speaking the verse. Read as many plays as you can. See plays, watch films. And above all else, speak his words out loud and be taken in by the story and .All this work will help turn Shakespearean from foreign language into beautiful, wonderful text.

If you want to learn more about acting check out our article on How to Act.

Leave a Reply