What is Subtext in Acting?

Words unspoken. Meaningful silences. Talking around the subject. In all of human interaction, subtext can be found wherever we need to convey our thoughts and feelings but don’t want to come right out and say them. In fact: as an exercise, think about how often you say exactly what you mean to a person you’re speaking to. 100%, literally, no skirting around it. Not often, huh? Thank goodness for subtext…

Subtext is something that every actor needs to understand: where to find it, how to create it and how to deploy it effectively. It’s a tool that brings depth to a performance, and allows for complex storytelling even if the scene has ten short words per actor. In this article, we’ll look at what subtext in acting is, how to identify it in a script and how to deploy it effectively as an actor.

What is Subtext?

Subtext is the term used to describe the underlying meaning of a piece of writing (the “text”.) In drama, it’s usually associated with a spoken line of dialogue, although it can be attributed to a stage direction as well.

Subtext relates to the true meaning of what is happening or being said; while it’s not explicitly mentioned, it nonetheless alters the significance of the text—or the meaning entirely. A simple line, such as “Get well soon!” may be infused with the subtext of the speaker hating the person they’re conversing with. The text, by result, becomes cruel, even menacing.

Subtext in Acting

Subtext has an important role to play in acting, as it allows actors to give insight as to their character’s personality, goals or motives without coming right out and Saying The Thing. It is important to identify Subtext in a script, so that the actor knows what the writer is intending with their character and doesn’t miss the point of a scene. If two characters sit and talk about the weather as they wait for their execution by firing squad … you can bet there’s more to the scene than clouds in the sky.

Russian theatre practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski spent a lot of time on the concept of subtext, offering to his students the helpful tools of using intonation, gestures, pauses and stillness to convey it. To Stanislavski, words were like the tip of the iceberg in human interaction: only ten percent of thoughts are spoken, with the other ninety percent remaining unsaid.

Most importantly, subtext allows actors to pursue their objectives in interesting and truthful ways. If your character has a goal to borrow $10 from a friend and their first line is “You look well!”, not using that with the subtext of “I need to butter you up because I need a favour” wastes that first line completely.

Subtext in theatre, identified and played, means that not a single line of dialogue is wasted.

How to Identify Subtext

Identifying subtext isn’t difficult in a script, although it can take some work. Much like analysing a script, the best way of finding it is to be thorough.

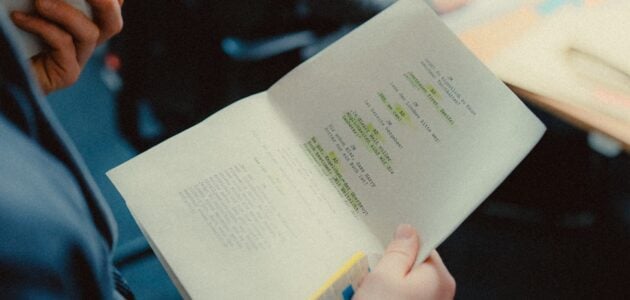

First of all, read the script and analyse it. If you’ve yet to read our article on the subject of script analysis, jump to it now and come back when you’re finished. To identify subtext, you have to know everything about the characters: who they are, what they want (the objective) and how they plan to get it (the action.)

Once you’ve read and thoroughly interrogated your script, look to your character’s dialogue. What is being said? And what is not being said?

Example

Let’s say the line we’re looking at is this:

ANGELA

Have a wonderful flight.

Aww. She seems nice, doesn’t she! But is there subtext to be found? For this, we might need to read back earlier in the scene:

EXT. RUNWAY – NIGHT

ANGELA picks up the last of her employer’s many bags and loads them into the storage compartment of the small plane. Her employer, DAPHNE, talks incessantly on her phone as she approaches the door of the aircraft. ANGELA smiles at her boss. DAPHNE walks past her, ignoring her completely.

ANGELA

Have a wonderful flight.

Suddenly, there are more questions about the delivery of this line. Sure, it’s only four words. But are they delivered sarcastically? Politely? Sadly? Defensively? Let’s do one final flip back through our imaginary script:

EXT. HOTEL ROOM – NIGHT

ANGELA, still crying, lets herself into her boss’s hotel room. From her jacket, she removes a small explosive device, which she slips into the largest of DAPHNE’s luggage.

And now “Have a wonderful flight.” takes on a whole new meaning. The line, on the page, is polite—even cheerful! But the subtext is “Goodbye, and good riddance.”

Subtext is hidden within the text. It’s not always obvious to see. But remember that your character’s objective is harder for them to mask. In this example, Angela’s objective is to kill her boss. While the line of dialogue doesn’t suggest that right off the page, the subtext informing it is fairly clear once you’ve done some digging.

How to Create Subtext

As an actor, you can’t “create” subtext, so to speak. What you can do is let your character’s wants (their objective/s) inform how they say what they say or do what they do. Again: what is being said? What is not being said?

If you try to manufacture subtext, you run the risk of making choices that aren’t supported by the character or the script as written by the writer. Some actors feel as though subtext is the guaranteed way to make a scene more interesting. If they play every line like they’re secretly a hitman and they want to kill the person they’re speaking to, then presto! the scene will instantly be gripping to an audience.

This is a terrible idea. Don’t let yourself become informed by subtext that can’t be suggested or supported by the script. Subtext can’t exist without text. Always return to what is written and ask yourself what the writer intended. Good writers will write subtext into their work. It may be buried deep, but it will be there.

Subtext and Shakespeare

Finally, let’s discuss a common misconception about the work of William Shakespeare. The rule goes: there is no subtext in Shakespeare. Everything he wants you to know is written plain on the page.

In truth, the relationship between subtext and Shakespeare isn’t so simple. While it’s true that Shakespeare’s language is clear and descriptive, it’s also not without room for actors to interpret: especially when it comes to a character’s true intentions (objective) and how they might be subverted.

Shakespeare used imagery, metaphor, double entendres and puns to hint at hidden meaning beneath text. Take this classic example from Hamlet:

HAMLET

Lady, shall I lie in your lap?

OPHELIA

No, my lord.

HAMLET

I mean, my head upon your lap?

OPHELIA

Ay, my lord.

HAMLET

Do you think I meant country matters?

“Lie in your lap” and “country matters” both refer to, well, if you’re not sure ask a grown-up. And yet the language itself is far from explicitly sexual.

With Shakespeare, look for hidden or layered meaning (whether you call it subtext or not) by examining the script, learning to ‘decode’ his words and looking to the objectives and actions of the characters. We’re not here to disparage the “there is no subtext in Shakespeare rule.” But we do think it’s best to be aware that there is more to the language than it reads off the page. It’s up to you to find it.

Subtext in Screen Acting

Everything that we has been discussed so far can be easily transferred into your screen work. However, when working on camera, subtext in acting is even more essential. The camera is like a lie detector, picking up every tiny nuance in your expression. Because the camera allows us into your inner world, your subtext here can be even more subtle. On screen, simply having the thought, will read clearly. This means that when you are working on screen you need to make sure you have crystallised your acting choices and really understand the inner monologue of your character. Never feel like you have to “show” your subtext, and trust that if you are connected to the text that it will come through.

Conclusion

What is subtext in acting? It’s the good stuff: the gooey, complex workings that bring depth to characters and story. While it’s not always easy to identify, just remember that it’s there to help you. And so once you can find it and play to it, subtext will always support your performance and enhance the choices you make. Good luck!

Leave a Reply