Script Analysis: How to Get the Most Out of a Scene

Picture this: you’re sitting in the lobby of a powerful casting agency. You’re surrounded by ten other nervous-looking actors who look just like you, are dressed just like you and have prepared exactly the same scene as you. You look around, they all look back: it’s like a fun-house mirror at a carnival. How the hell are you supposed to set yourself apart?! Our recommendation is to invest in your script analysis skills: the best secret weapon in any actor’s tool kit.

Script analysis is a process by which actors interrogate a script for its intended meaning. It consists of equal parts research, close-reading of the text and guess-work: determining what a writer is trying to say, as well as the ways in which one might interpret the words to create an original and dynamic performance. Cohesive script analysis ensures that an actor has a clear understanding of the script’s narrative as well as their character’s individual arc, personality and relationships.

In this article, we are going to talk through several important tools for script analysis. The list below is, by no means, exhaustive, but will help you on your journey to better engaging with and understanding any given text. Remember: every actor works to a slightly different method that best supports their process; as you develop your own, always look to your peers for the opportunity to learn new tools that provide greater insight.

Updated 13th December, 2022.

Jump to:

- Reading the Script/Textual Analysis

- Assessing Stage Directions

- Find the Facts, Ask the Questions

- Focusing on Your Character

- Finding the Beats in a Script

- Determine Your Objective

- Plot Your Actions

- A Case Study: “The Pawn Shop”

Reading the Script/Textual Analysis

Know the text. Know every word and how the author has put them together. It might seem redundant to stress the importance of reading the script in an article about script analysis, but it’s something that far too many actors fail to spend enough time on. Not knowing and understanding the words on the page always comes across as unprepared and uncaring; it’s a killer in auditions, especially in a drama school context. As you start analysing, asking questions about the scene and making choices that inform your character/performance, ninety-nine percent of your answers will come from returning to the text, over and over, and seeing what the writer has left there for you to discover.

- Word Choice. A writer will justify every single word they put down on a page: ask yourself why each of them is there. Note interesting and unusual words; look for adjectives and adverbs that offer description or modify other words or parts of a sentence. Verbs will eventually help you discover objectives, and plot the actions you’ll need to pursue them. It’s also worth asking why certain words aren’t used. Why does a character say they’re “very upset”, and not “devastated”?

- Punctuation. Punctuation marks are the way writers direct actors off the page. Look to them for indicators of energy, pace, how your character is reacting in a scene and how they process new developments. Are sentences short and lacking description? Could be the scene is tense. Are they flowing, using commas to break up the action, in order to create a sense of rhythm? Perhaps there is more emotion, or an underlying subtext you’re being asked to discover. At times the author might use a long run-on sentence, full of confusing (or even misleading?) punctuation marks—a sentence full of small breaks in a larger thought—that show you, the actor, that your character is processing information in a scattered, terrified manner?! You will often find more interesting provocations studying the punctuation of a scene than the words themselves.

- Structure. How is the scene set out? Is there a lot of description, or does the author get into things fairly quickly? Is there a lot of ‘white space’ on the page, or is it text-heavy? Paragraph breaks are a great thing to note, especially when you are starting to break down the text into individual “beats” (see Finding The Beats in a Script, below). Is a new paragraph a new thought? A pause? Is it intended to create tension, or give the audience release? Does reading multiple, short paragraphs speed up or slow down your reading of the scene Should that be something that informs your performance?

- Style. Is the author writing in a particular style? A dialect or patois? Are they trying to emulate another author, style or time period? How might this inform your reading of the piece, and your greater understanding of their authorial intentions?

It’s worth mentioning, at this juncture, that any one of the tools we’re talking about in this article can be useful at any stage of the analytical process. Don’t think you’re done with reading the text just because you’re now thinking about action and objective. Each of these tools strengthens the performance of the other.

Assessing Stage Directions

“Just cross ’em all out.”

It’s sad we even have to mention this: don’t scribble out stage directions/big print an author has written into the text—probably after multiple drafts and interrogations by editor and publisher (and themselves) alike. Stage directions are something we’ve spoken about in more detail elsewhere on the site, and there are entirely valid schools of thought on how literally they should be taken. In a script analysis context, ignoring them completely can rob you of important clues left by the writer on how a scene should play out. Even if you plan on cutting or modifying them, give thought as to why they have been included. And, at the very least, try the scene as written to try and determine what their intended effect may have been.

Our relationship with stage directions/big print is also different across different media. This article focuses primarily on the screenplay format, but its lessons are the same for theatre scripts. The thing to remember with plays is there is no hard-and-fast structural rule for writing them as there are with movies—nobody’s throwing a play in the bin because the margins are wrong, they probably think it’s “art” and “a choice.” So your job, when analysing a play script, is to interrogate why it has been written in such a way. Samuel Beckett was famous for his stage directions that have to be followed to the letter (or you risk legal action. Seriously.) But is he any better a playwright than Shakespeare, whose stage directions are famously loose? Or Sarah Kane, whose words are dotted all over the place in a seeming mess of chaos?

Find the Facts, Ask the Questions

Once you’ve performed as much textual analysis as possible, it’s time to start mining the text for definitive information, as well as places of ambiguity that will benefit from your own interpretation. One set of tools we can recommend are “Facts and Questions”, as proposed by seminal theatre director Katie Mitchell in her 2009 book “The Director’s Craft.” Start writing out a list of facts about the script: anything you can definitively prove by referring to the author’s words. Here’s an example:

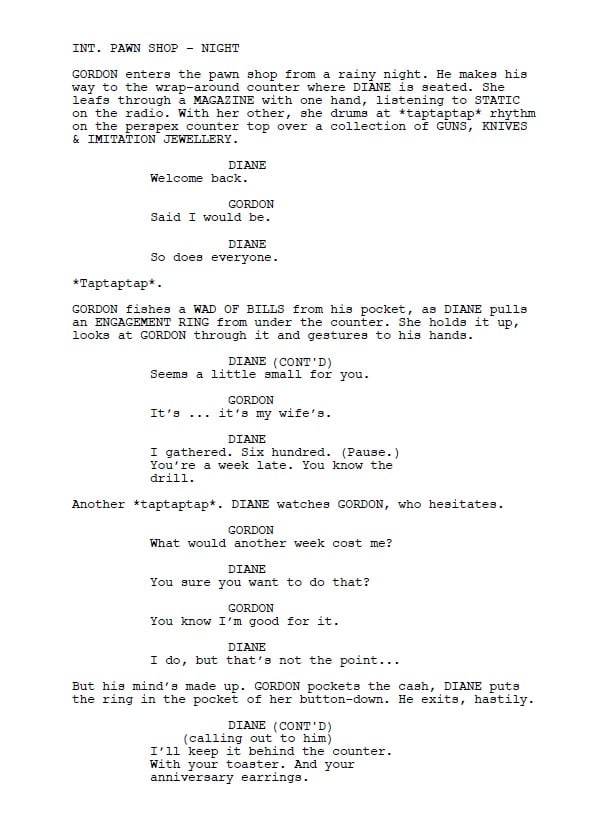

INT. PAWN SHOP – NIGHT

GORDON enters the pawn shop from a rainy night.

What facts can we determine from this (admittedly short) excerpt?

There is a pawn shop.

It is night time.

It is rainy.

There is a person named Gordon.

Gordon has entered the pawn shop.

At this point, we have to avoid making assumptions. Say were were playing Gordon, and wanted to get a sense of his mood, perhaps some ‘moment-before’ insight. Is Gordon wet from the rain? Ostensibly, yes: he’s just walked into the pawn shop from a rainy night. But maybe he has an umbrella he stashed by the front door? Maybe he held a newspaper over his head as he ran from his car. Is that how he got to the pawn shop? Or did he take the subway? If so, where’s the station? Where’s the pawn shop?

Now we start getting questions to add to the list:

How did Gordon get to the pawn shop?

Is Gordon wet from the rain?

If not, how did he protect himself from the rain?

Does Gordon own an umbrella?

Questions usually give rise to other questions. This is how your analysis starts going from purely factual to highlighting the areas you can explore with your director/scene partner. These are the areas where you can put your personal spin on the scene, without treading on the existing facts that allow the story to function in a logical sense.

Focus on Your Character

With a firm grasp on the larger context of the scene, you can now start focusing on your particular character and their arc. Facts and questions will definitely help you along with this, but there are other tools that you might find beneficial. Determining your character’s Given Circumstances is a great way of honing in on their place within a scene/script:

Who am I?

What time is it?

Where am I?

What surrounds me?

What are the given circumstances of the past, present and potential future?

What are my relationships in the scene?

What do I want?

What do I do to get what I want?

As you might have noticed, the two final questions will lead you seamlessly into your plan of attack for all things action and objective. Consider how much more information you have to work with at this point in the script analysis process, than an actor who had performed one or two cursory reads of a scene before jumping into plotting their performance.

Finding the Beats in a Script

Beats are a term in acting/script analysis so widely used that they defy any one definition. They are scenic gear shifts that can denote a physical change, a change in a conversational topic (that is, to say, a scene’s direction) or even a change in energy/emotion.

Beats are often tied up with the actions played in a scene; a new beat can signal the need for a new action as something in the status quo of the scene has shifted. You will find determining beats (and, therefore, actions) much easier after analysing a script—especially its text. Just remember that a beat change doesn’t always call for a new action: play a new action as you either achieve your objective or exhaust the effectiveness of your last choice.

A good scene, whether dramatic or mundane, is a point of no return in a story. Something in that moment changes, no matter how small on the surface, and propels the story forward (else it has no reason to be there.) The same can be said for beats within a scene: look for the turning points in a scene where what is said or done can’t be wound back. This will lead you to discover the dramatic tension—and how you might ratchet it up.

Determine Your Objective

The question of How To Find Your Character’s Objective is central to any actor’s performance, as it is what drives their character to make decisions and take part in the story’s overall narrative. Therefore, your character’s objective should, scene-to-scene, be relatively straightforward to determine. Ask yourself: “What does my character want in the scene?” If the scene contains more than just your character, ask: “What does my character want in this scene from this person?”, as your objective should always have you engaging with your scene partner.

It is at this point that a lot of actors make a crucial error: don’t confuse an “objective” with a “super-objective”. Don’t search for a grander narrative than the one in front of the character in a particular scene. Take our above excerpt:

INT. PAWN SHOP – NIGHT

GORDON enters the pawn shop from a rainy night.

What could we say Gordon’s objective is? (Again, we don’t yet have much to work with.) “Gordon wants to enter the pawn shop.” We may later learn that Gordon wants to raise money for a career in stand-up. But even if that’s the case: right at this moment, he wants to walk through the door, not “Become the greatest comedian of all time”. Don’t confuse “objective” with “intention”, which speaks more to the “why” of an objective than the “what”.

If you can plot your character’s objective from scene to scene (or shorter, if the character ends up pivoting in a scene or achieving their objective early), you’ll start to get a stronger sense of the character’s overall arc. You may find them driven by a larger super-objective, but each objective is what brings conflict and, therefore, drama, to the script. Crawl before you walk or run, else your character will end up tripping over their own feet.

Plot Your Actions

Once your objectives are clear, you can begin your work Plotting Actions. Actions are the “how” you achieve the “what” of the objective: how you actually play the scene as your character pursuing their goal. This is where much of your earlier textual analysis will really pay off: word choices around verbs, adverbs and adjectives will help you consider what actions will play the strongest.

Plotting actions can be a tough process. From a script analysis standpoint, you can spend as much time on this one step as the entire rest of the process! But look for new actions in each thing your character says: each line, each sentence, even half way through a sentence if you feel your scene partner might react! Why? Because when we speak to other humans, we play different actions for every new thing we say: we might plead one moment and then guilt the next! Plotting individual actions per scene is going to bring your performance to life, as that’s exactly what real people do.

Another important factor in plotting actions is your character’s relationship with their scene partner. What do you know about their shared history? What can you determine about their relationship? How might your character act/react that is singular to this person? (We provide an example of a relationship breakdown in the Case Study below.)

Your actions should always be interesting, but also related to how best your character might achieve your objective. Again, look to your textual analysis, your facts and questions to determine which actions will feel natural and which will jar. This doesn’t mean that you can’t make unexpected, totally-left-of-field choices! It means that those choices will always have a grounding logic in the script itself.

A Case Study: The Pawn Shop

Now that we’ve talked through the foundational aspects of script analysis, let’s tackle an example to see the above tools in action! You might like to try analysing this script yourself, or simply skip down to the answers provided below. Do keep in mind that you may have a completely different interpretation, or see significance in aspects of the text that we barely touched upon. Any and all answers are valid if they are supported by the words on the page. Good luck!

Textual Analysis

Stylistically no-nonsense. Language not very descriptive.

“taptaptap” some kind of recurring rhythm. Visual/aural motif?

“GUNS, KNIVES & IMITATION JEWELLERY” an interesting detail. Foreshadowing?

Sentence structure is short, informal between characters. Do they know each other well?

Ellipsis (…) for Gordon. Indecisive character?

Note: (Pause.) in Diane

Some single-sentence big-print. Possible beat changes?

Facts & Questions

There is a pawn shop.

It is night time.

It is rainy.

There is a person named Gordon.

Gordon has entered the pawn shop.

How did Gordon get to the pawn shop?

Is Gordon wet from the rain?

If not, how did he protect himself from the rain?

Does Gordon own an umbrella?

Diane works at the pawn shop.

Diane is seated reading a magazine.

The radio is on.

Diane taps her hand on the perspex counter.

There are guns, knives and imitation jewellery on display.

Diane welcomes Gordon back.

Gordon says he would return.

Is Diane cynical of this?

How well do these two know each other?

Gordon takes money out of his pocket.

How much money does Gordon have?

Diane takes an engagement ring out from under the counter.

Is the ring really Gordon’s wife’s?

Diane says the price has gone up because Gordon is late.

Why does Gordon hesitate?

Does Gordon really not know what another week of not getting the ring back cost him?

Why does Diane seem unwilling to keep the ring?

Does Diane know Gordon’s wife?

Is Gordon actually married?

Gordon pockets the money.

Diane puts the ring back in her pocket, not the counter.

George exits hastily.

Diane calls out after him, perhaps to mock him? Or comfort him?

Has Gordon really pawned all of these items?

Gordon Character Notes

“Gordon strikes me as an indecisive, desperate man. While his relationship with Diane seems strained, there is a camaraderie there by the way she seems to bend the rules of her job. He seems to need money, and yet he’s got a load of cash in his pocket to buy back the ring suggesting that when push comes to shove, he can get his hands on some.

One of the most interesting things about this guy is his confidence: almost cocky. When posed with the choice to let go of the money or keep it, he’s quick to sacrifice the ring. “DIANE watches GORDON, who hesitates.” is a moment worth some consideration.

Gordon seems deeply indebted to Diane. He also seems to lean heavily on his wife and her possessions for financial gain. It will be interesting to see whether or not she has any idea of his activities that require him to pawn items for quick cash.”

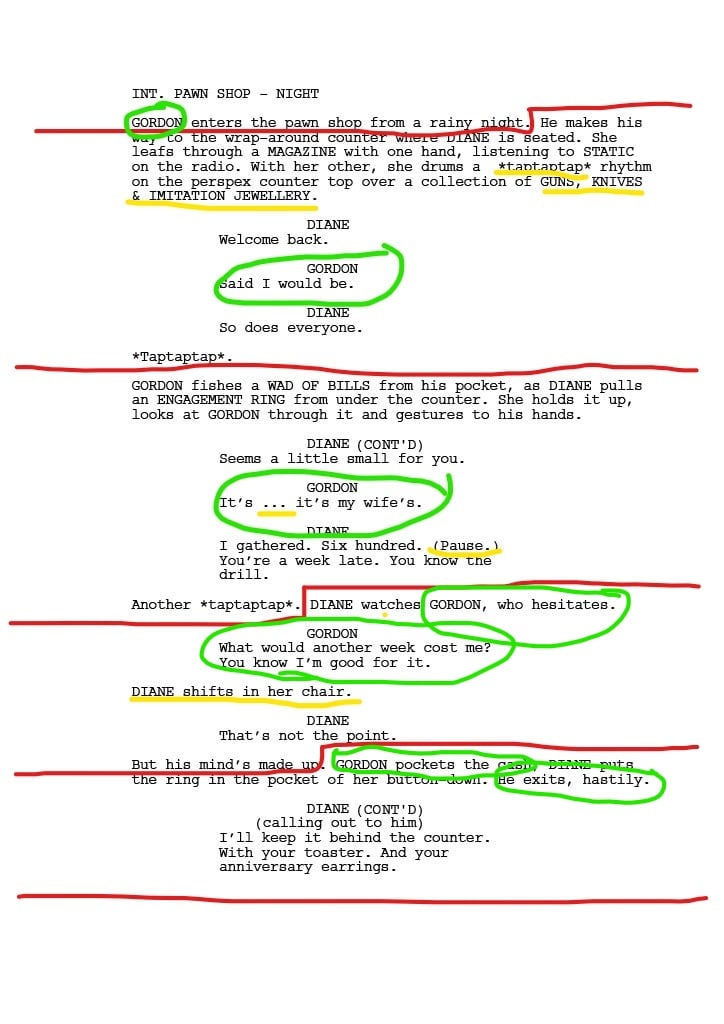

Script Breakdown: Beats, Textual Analysis and Character

Here we have an on-page breakdown, where red denotes beat changes, yellow signals textual points of interest (listed above) and green highlights our character focus.

Objective/s & Action/s

Gordon seems to have two objectives in this scene:

Gordon wants to buy back the ring from Diane.

But something changes in the fourth beat. Gordon hesitates. Having seemingly achieved his objective, he tacks to a new thought/idea. Subsequently, his new objective is:

Gordon wants to convince Diane to give him more time.

Next up are possible actions, separated by the beats above. We’ve listed a few options, where applicable, but actions are best chosen in the rehearsal room with the input of your scene partner and director. Be ready to defend an action choice as whether or not it suits your character. Your script analysis will help you justify your choices with objective truths you have learned directly from the script.

Beat 1 (When Gordon enters the pawn shop): CHARM/BLUSTER/IMPRESS/INTIMIDATE?

Beat 2 (When Gordon speaks to Diane): Any option here will help us determine his relationship with Diane. As the above four still fit in this context, it’s probably best to perform an escalation of one of these.

Beat 3 (When Gordon pulls out the bills): Gordon gets on the defensive, here. He has to justify selling his wife’s ring: APOLOGISE/EXPLAIN/REBUFF/MAKE LIGHT OF.

Beat 4 (When Gordon hesitates and pockets the bills): Beat 4 is also where we see a shift in objective. It is important that there is also an action-shift, here, as the character has new wants and must have new tactics to get them: CONVINCE/DEFEND/ATTACK/STONEWALL

Beat 5 (When Gordon leaves): Again, these can be an escalation of the Beat 4 action choice. Gordon needs to double-down, to bet on himself in this unexpected moment.

Conclusion

This might seem like a lot of work to do for a single page of script—especially when it might be one of a hundred or more in a feature screenplay! But take our word for it when we tell you that script analysis is an enriching process for any actor: one that rewards a deep-dive into text with a greater understanding of how to bring your character to life. Learn to love the detective’s game you play as you unpack the author’s hidden ideas and layered meanings. And the more script analysis you do, the more you’ll realise that it’s a part of the actor’s skill set you can not function without. Invest in these tools, hone them and sharpen them, and you are guaranteed to separate yourself from the rest of the pack.

Leave a Reply