The Stanislavski Method

There’s a reason that the “method” is so revered, utilised and taught in studios, stages, sets and institutions around the world. The Stanislavski Method is, in its essence, the amalgamation of every piece of acting wisdom that theatre practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski knew of and hunted down. Because of that, it is long in scope and immense in breadth. What Stanislavski did was take all of the best bits of acting advice and methodology from practitioners and teachers alike that he could, mixed it with his own work as a director, actor and teacher, and distilled it into what he believed (and what many others do too) to be the core fundamentals of acting.

Updated 5th October, 2022.

Most acting training at drama school is based, at least in part, on Stanislavski’s teachings. But even after years of rigorous training, there are still things to be learned, honed and discovered. Given that the method is, let’s face it, gargantuan in scope, this article should give you an outline of the key principles—so that you can continue your investigation from here and dive into everything he gave us.

Who was Konstantin Stanislavski?

Background

Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavski was born in 1863, to a wealthy family in Moscow. While his extreme privilege afforded him ample resources to study the craft of acting and performance, he didn’t appear as a professional actor until age 33 (the name “Stanislavski” is actually a stage name used to shield his family from public humiliation). Even before his professional debut, Stanislavski still managed to establish himself as a celebrated character actor; however, he best distinguished himself from his peers as a keen and constant student of his craft. He would study with the foremost acting teachers of the time to develop his own understanding of acting, and even keep notebooks filled with criticism and recollections of his performances. These would later inform much of his teaching and writings on the subject of acting.

Moscow Art Theatre

After years of amateur and professional distinction in his career, Stanislavski cemented his place in theatre history by co-founding the Moscow At Theatre (MAT) in 1897 with director Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. The MAT became internationally renowned for their work in naturalism: crafting realistic characters and situations, that contrasted with the more ‘theatrical’ performances the public were used to seeing on stage. They helped establish emerging Russian actors and writers, including the plays of Anton Chekhov.

MAT was the prominent state theatre company of the late Russian Empire; this position was maintained throughout the Empire’s end and into the creation of the Soviet Union in 1917, although its budget was severely affected by new economic policies. However, this led the MAT to tour America a number of times, where it was seen by such practitioners as Lee Strasberg who were inspired to bring naturalism to American acting (and trained a generation of stage and screen juggernauts).

Stanislavski the Teacher

In addition to his work as a theatre director and leader of the Moscow Art Theatre, Stanislavski constantly worked to refine his teaching methodologies. He founded his first teaching studio in 1912 (called, helpfully, the “First Studio”), which was concerned not with the initial training of actors but the continued refinement of young, established professionals.

In 1926, Stanislavski published the first volume of his teachings titled An Actor’s Work—a manual framed as an acting student’s journal (much like those he kept growing up). The plan was for three volumes: one on the inner characterisation, one on the outer and one on the process of rehearsal, which Stanislavski would write and subsequently publish as they became ready. However, a 1936 heavily-abridged English translation called An Actor Prepares only covers the psychological aspects (first volume) of his methodology. This was one of Stanislavski’s concerns with the publishing strategy, as he feared readers would misinterpret one-third of his teachings as the entire methodology.

While efforts continued after his death in 1938, Stanislavski’s entire teachings were finally collated and published in 1957—the closest English language version appearing four years later. A complete English-language version of An Actor’s Work was finally published in 2008.

What makes Stanislavski so Important to Acting?

Beyond the development of a brilliant methodology (which we’ll explore in detail below), Stanislavski’s lasting influence was his role in popularising naturalism in theatre—a style that spoke to the genuine concerns and emotions of the audience. Even when playing or directing the classics (Stanislavski was a fervent Shakespeare fan), he would bring his same process to the role, making a fake king from a distant land and time feel real.

It can be difficult for us to grasp just how influential Stanislavski was; this is partially because the system that he developed is de rigeur in theatre, film and television today. Iit’s strange to think there was a time when actors didn’t, well, act in the same way they always have in our lifetimes. When Stanislavski toured America in 1926, his teachings and philosophies led to the founding of the Group Theatre in New York. The Group Theatre gave us—among a constellation of stars, directors and playwrights—the three American giants of acting teaching Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner. And their students (literally everybody) brought naturalism to Broadway, Hollywood and then the world.

Stanislavski Acting Training

When it came to acting training, Stanislavski aspired for actors to be highly-skilled blank canvases. The whole idea was to be open and free so, when presented with a quality piece of text, the body, mind and spirit were all prepared to run wild (but with fine craft).

The key principles behind Stanislavski’s thoughts on acting training are these:

#1 Psycho-Physicality

The most basic premise of PSYCHO-PHYSICALITY is that your mind and imagination are connected and rooted to your physical body and vice versa. When one goes this way the other goes the same, and so on and so forth. This is one of the key principles in most actors’ practice and, as far as we’re concerned, one of the most valuable tools in the kit. When your mind and body are connected there is a sense of flow to your acting; when your craft is honed enough, you can simply follow your imagination wherever it wants to go.

#2 Discipline

In brief, what Stanislavski meant by DISCIPLINE was that you need psychological discipline to help you determine the differences and similarities between yours and the characters’ minds. You need physical discipline to train your body rigorously, you need imaginative discipline to colour your skill with your imaginings, and you need a sense of collective responsibility for you and your fellow castmates so no one ends up with a sword in their eye. (Trust us: it happens.)

#3 Stage Ethics

This one is pretty self-explanatory: how you behave in and out of the theatre, and your relationships to your other creatives. It’s pretty simple, really. Stanislavski believed that you had a responsibility not only to yourself, but to everyone around you to show up prepared, do your work and be respectful of everyone involved. This isn’t just about being dictatorial, it was about how it affects the performance.

“If one person is late, it upsets all the others. And if all are late your working hours will be frittered away in waiting instead of being applied to your job, that makes an actor wild and puts them in a condition where they are incapable of work…”

#4 Relaxation & Breathing

This is the first hands-on physical tool Stanislavski’s method employs. Once the body and mind are relaxed, we can be more open and allow us to enter what he called the “Inner Creative State”. More on that later. If you’re not breathing and in a state of relaxation, one, you’ll die, and two, your “Blank Canvas” will be filled with holes before you even stick it on the easel.

For more about relaxation and tension, check out Actor’s Worst Enemy: Tension

#5 Concentration and Attention

When we are in the relaxed state, that doesn’t mean we float off into LaLaLand ©. It means that when it comes time to pinpoint our focus, we are ready and not thinking about if we do or do not want pickles on our sandwich for lunch. The basic principle is that you can’t work from a state of tension—be it physical or mental.

Stanislavski’s Four Conditions of Acting Practice

Stanislavski had four conditions of acting practice which he believed made way, and allowed for, the best possible outcome from the production, the page, and the performer:

The first of our four conditions is INSPIRATION. You know when you get your hands on a script for the first time and your imagination just runs completely unimpeded and wild? That is what we’re looking for when we talk about inspiration. What gets your creative juices flowing? What lights up your mind? This will be what drives you from the first read to closing night

For more on: Finding Creative Inspiration.

The second is SPIRITUALITY. A close cousin to inspiration, spirituality is yet another part of what makes a performance whole. Spirituality was Stanislavski’s own way of saying what most practitioners have said and continue to say: you must be alive, right here and right now, to bring a life onto stage. And how can you explore the soul of a character if you haven’t explored your own?

“An artist must have full use of their own spiritual, human material because that is the only stuff from which they can fashion a living soul for their part.”

When we talk about a CREATIVE ENVIRONMENT, you probably already have a pretty clear idea in your mind of what that’s like, right? Think of an open and safe environment where you can play, explore and dig deep into whatever work you’re doing. If your rehearsal environment is busted, your performance will be busted as well.

Finally, we have the INNER CREATIVE STATE. There’s a lot of reading to be done on the inner creative state; in it’s most basic form, it’s all about nurturing a ‘creative environment’ inside of yourself. We talked about how our creative environment should be safe, playful and open and free, right? Well, that’s the environment we should be trying to create within ourselves! This allows us the opportunity, to play and explore with an open mind, body and heart and deliver the best performance possible.

The concept of the inner creative state is also something that counteracts a lot of silly opinions that Method acting is somehow “dangerous”, or edgy. Utilising Stanislavski’s Method—or any subsequent Method inspired by his teachings—is never about letting go of control. It’s always about keeping control, anchored by a mental and physical wellbeing that ensures the actor is always safe.

The Stanislavski Rehearsal Process

Mining the Text

Dive deep into whatever text it is you happen to be working on and figure out what’s going on. There are a number of tools in the method used to do just that. This usually begins with the first read: the first read should really be kind of sacred. Even if you’re not going to light candles, dance around the script and/or sacrifice something, there needs to be given some level of levity and respect for the first time you read a script.

However, we understand that’s not always possible, particularly with the kind of schedule actors tend to lead. But it’s something to think about and invest in as much as you can. It could be as simple as making sure you block out the time to give the script a full read, along with a bit of time afterwards to let your imagination drift and jot down your initial thoughts (first impressions matter).

For more information on mining the text, check out: Script Analysis and How to Break Down a Scene.

Mining the text also means figuring out the given circumstances. For this, we will consult the almighty SIX FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS:

Who: Is in the scene?

When: Does it happen?

Where: Does it happen?

Why: Does it happen (which takes you into structure and objective)?

For what reason: Does it happen (which leads you deeper into imagination and justification)?

How: Does it happen (will ultimately become clear on the floor)?

You’ll also be looking for OBJECTIVES and COUNTER-OBJECTIVES, as well as breaking down the actual structure of the piece: how many scenes and acts, all the way down to beats, pauses, and even punctuation. There is a lot to discover in the text alone. Playwrights don’t just chuck a play together and hope for the best; there is a reason for everything and, ultimately, you can always discover more. Particularly when you’re working with a quality piece of text.

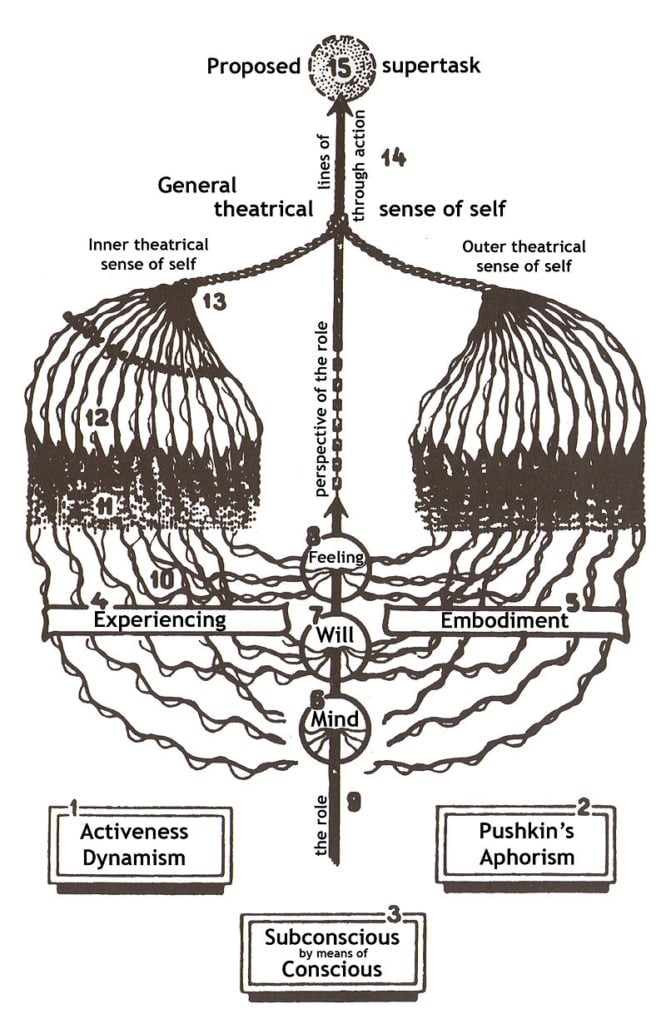

Diagram of Stanislavski’s ‘system’, based on his “Plan of Experiencing” (1935), showing the inner (left) and outer (right) aspects of a role uniting in the pursuit of a character’s overall “supertask” (top) in the drama.

Uta Hagen is another practitioner who does a lot of work on Given Circumstances. You can read an article about her approach here: What Are Given Circumstances?: Uta Hagen.

Embodying the Role

Having mined the text, the next part of the rehearsal process focuses on embodying that role. This is where you take everything in your mind and let it flow through you to create a living, breathing character. There’s a myriad of tools Stanislavski gives us to do just that.

The first thing you’ll want to do is start to build a sense of TRUTH. Truth does not necessarily mean absolute naturalism in this school of thought. While Stanislavski paved a good part of the path to our more modern and naturalistic style of acting, what he prescribed and taught was seeking a sense of scenic truth. Scenic truth is a fine balance of experiencing what the character is experiencing and applying fine craft to make it understandable and watchable. To do this, we go back to our imagination and use the power of observation in the world around us—along with Stanislavski’s MAGIC IF.

First thing’s first: the Magic If is not substitution. You are not using your own memories to connect to what you’re doing but rather, once again, your imagination. What would I do IF my dog started talking to me? What would I do IF I’d just lost my job? What would I do IF I ran out of examples to give in my article on Stanislavski? This will give you a real and tangible idea of a character’s actions and reactions that will propel you further into their mind.

You can learn more about the ‘Magic If’ in our article about Emotional Recall vs Sense Memory.

Each of these tools are used inherently to find an inner and outer sense of truth. Once you’ve achieved that, you can look to bring alive your Psycho-Physical senses.

The first of these we’ll cover is ACTION: how you go about obtaining your objective. If my objective is to seduce, then an example of my action could be to place my hand on the other character’s hand, or to flirt, or even to tell a joke.

The next tool is TEMPO-RHYTHM. Stanislavski said:

“Wherever there is life there is action; wherever action, movement; where movement tempo; and where there is tempo there is rhythm…”

Tempo-Rhythm is an inherent part of life. How do you feel when you see a spider? How do you feel when you see a friend? These are examples of real-life Tempo-Rhythm: the speed at which you execute your actions both inside and outside—and they are not mutually exclusive. The way you feel inside might be vastly different to how you present externally. It’s important to identify how your character would be feeling and living in each moment, particularly if they differ.

The other way we build on our Psycho-Physicality is through exploring EMOTION and EMOTION-MEMORY. In brief, emotion memory is your storeroom as an actor and can be used to bridge the gap between being on the outside of your character looking in, to being one with your character. It’s quite similar to the Magic If, except that you are looking inward to your own past experiences, not into the ether of imagination to propel you into a psycho-physical response.

Character and Characterisation

Now that we’ve taken a look at the building blocks of embodying a role, let’s look at a few tools that should help you tackle character and characterization. We’ll start with INNER PSYCHOLOGICAL DRIVES: our thought-centre, our emotion-centre and our action-centre. Each of these drives us in a different way, with a different motive. They can be thought of as anchors, either simultaneously pulling us in one direction or all over the shop at once.

“Three impelling movers in our psychic life, three masters who play on the instrument of our souls.”

When we have differing Inner Psychological Drives, we find ourselves in a state of HEROIC TENSION—the ‘other side of the coin to the character’. Everyone thinks of Hamlet as a brooding and melancholic figure, but it is just as important to find his lighter side. Stanley Kowalski is a brutish figure, so it is important to find his moments of softness and vulnerability.

There is also EMPLOI, which is what a character does with their time. If they have a job, this will affect how they go about their day-to-day life, what they think about, and what drives them. It’s just as important to note if a character doesn’t have a job, such as Marsha in Chekhov’s Three Sisters. If she doesn’t have something that occupies her time, this will affect how she feels, what she does, and how she does it.

Do you have a favourite coffee mug? A sentimental piece of jewellery? A phone that seems to be an extension of your hand at this point? Another thing to think about and utilise when you’re embodying a role is the physical OBJECTS your character surrounds themselves with. These all hold miniature relationships to the character, and you should explore them. You should also identify when your surroundings and the objects around you are unfamiliar.

The last piece of this section requires some sense of levity. When it comes to Stanislavski’s idea of the SUBCONSCIOUS, it’s really something better experienced than explained. When all of your prep is done, and you’re raring and ready to go, one of the hardest things you have to do is let go. If you’ve done the work, spent the time and really explored this character, when it comes time to get on the floor your subconscious should be able to take over. This allows us total creative freedom. It is informed, but it’s completely free, and you’ll find yourself making choices and going places you never would have imagined.

Approaches to Rehearsal

Stanislavski had a LOT of thoughts when it came to rehearsal methodology; as with the rest of this article, this section is more a summary intended to give you the gist than an in-depth analysis of the concepts. The most important thing to take from this section, if you take anything, is that no matter how much prep you’ve done, no matter how much homework, you aren’t going to know what’s going to happen until you put your work into a rehearsal context and you are bouncing off of the ideas of your director/castmates/creatives. This is paramount. We are always in collaboration, and it is the artists that you work with together that will really make the work shine. It’s just your responsibility to be ready.

Here are the tools that Stanislavski employed in the rehearsal room:

- Étude rehearsals.

- Events.

- Grasp.

- Connection.

- ‘Here, today, now’.

- Justification.

- Adaption.

- Super objectives.

- Through-line of action.

- Verbal action.

- Pauses.

- The second level.

- Inner monologue.

- Envisaging.

- Moment of orientation.

There are some arguments between scholars and practitioners alike as to whether there is actually any difference between THE METHOD OF PHYSICAL ACTIONS and ACTIVE ANALYSIS. Our verdict here, is … to explore them and decide for yourself. That said, there are some key differences. The method of physical actions is an exercise which should allow you to go from simple physical actions to a deep understanding of the characters emotional and psychological life. Active analysis is a more regimented process, and goes a little something like this:

- You read the scene.

- You discuss the scene.

- You improvise the scene without further reference to the script.

- You discuss the improvisation before returning to the script.

- You compare whatever happened in the improvisation with the text.

Stanislavski Performance Practices

So you’ve gone through training, you’ve prepared as much as you can, now it’s time to meet the most important part of any performance: the AUDIENCE. Stanislavski had a great love and a huge amount of respect for the audience. He believed that as much as you should strive to connect with your scene partner[s], you should be striving for that same connection with your audience.

“We are in relation with our partner, and simultaneously with the spectator. With the former our contact is direct and conscious, with the latter it is indirect and unconscious. The remarkable thing is that with both our relation is mutual.”

When we talk about having two relationships coexisting on stage or in front of a camera, we’d be up the proverbial creek if we didn’t talk about DUAL CONSCIOUSNESS. Dual Consciousness is the process by which you essentially split your creative mind in twain. One is deeply invested in what’s happening on stage and living the life of the character, the other is focused solely in the real world. It’s focused on the lights, your marks and, of course, the audience. There should always be a balance between the two, and it’s entirely possible for that pendulum to get out of whack. The key is to always be seeking a balance between the two in your performance and not letting one overtake the other.

Another practitioner that spends a lot of time exploring the concept of dual consciousness is Yoshi Oida. Check out our article on his work: Why ‘The Invisible Actor’ is my Ride or Die Acting Book.

We’re getting to the very sharp point of the blade when we talk about your CREATIVE INDIVIDUALITY. In its most basic sense, it’s what you personally bring to the character—what no one else can bring to the table. Whenever you doubt your choices, or you don’t feel good enough in the role, remember that no one can do this as you can, and you’ll be fired up once again!

One last thing that Stanislavski talked about when it came to performance practices was INNER CREATIVE MOOD. This is the on-stage version of the inner creative state. It’s when you’re centred, and flowing and totally fired up. It allows you to let yourself fly.

Conclusion

While there may be no one perfect system, Constantin Stanislavski certainly spent a good chunk of his life trying to creat eone. His achievements in the art and scholarship of theatre and acting were immense, and there are few acting methodologies in use today that don’t owe him an enormous debt. With that being said, not every system will work for everyone. There might be bits and pieces in this process that you find suit you perfectly, and others that fail to light your fire. But that’s okay! The point of any system of acting is to produce the best performance possible, and how you get there is up to you. Good luck!

Leave a Reply