How to Write a Scene for your Showreel

It’s an all too familiar scenario. You’re missing out on auditions, your agent is harassing you and your online profile is gathering cobwebs. All because you can’t find the right scene for your showreel. “To hell with it!” you think. “I’ll write my own. How hard can it be?” Well, actually, fairly hard. But it can be done! So if you’re looking for tips on how to write a scene for your showreel, you’ve come to the right place.

If you want to learn how to write a scene for your showreel, start by setting goals that outline exactly what kind of scene you want. Once you’ve made some decisions, you can start to draft something that will fit the showreel format: nothing too long, too complicated, too dramatic, etc. As much as possible, have other actors read the material with you so you can hear it out loud and get an objective opinion. Try different versions with different variations, so that the piece you end up shooting is as tight as possible.

In my own practice as a writer, I create a lot of custom, tailor-made scenes for actors to put on their reels. It’s a little different from other jobs, because the focus is on the performer and not the material. So in taking you through this topic, I thought it might be interesting to treat you like a client. Let me walk you through the process as I would with any actor, and then you can try it out for yourself!

What Kind of Scene to Put on your Showreel

With all our focus on showreel and self-taping discipline at StageMilk (especially in our monthly Scene Club), we’ve covered this topic pretty well elsewhere on the site. Actors, when asking themselves what makes a good showreel scene, can paralyse themselves if not careful. It’s easy to spend your entire career looking for the perfect one, even while solid choices pass you by every day in the movies you watch or the plays you read.

To cover all bases, let me recap what you’re looking for in a good showreel scene:

- You want a short scene (max 60 seconds) that features you.

- From the very first frame, it needs to grab the viewer: prep for the casting director Too Busy And Important to watch more than fifteen seconds.

- The story shouldn’t be too complicated or involve too much plot or backstory.

- It shouldn’t be too dramatic: no screaming, no crying.

- Finally, make it something that is a good fit for you. Is it indicative of the kinds of roles you’d like to play, or think you’d do well?

Beyond the scene itself, ensure that the entire showreel consists of three, punchy clips that exhibit you range. A good showreel is like a great mix-tape. But that’s another conversation again. Let’s return to the task at hand and write you something good…

What Kind of Scene do you Want?

When I work with actors, the first thing I ask them about is tone. Is it warm? Cold? Do you want the audience to be delighted, depressed, inspired or amused? I like to start here because it gets you thinking beyond the content, or even the genre, to the feeling. And that’s what a good showreel is all about.

Showreels give agents/casting directors/producers the chance to get a sense of who you are, what kind of work you’re drawn to and what you’re like to work with. It’s why I often recommend actors use material they’re proudest of, rather than some huge gig they may have done that only features them for a few seconds. You got killed by fungus in episode 5 of The Last of Us? Cool! But a split-second death scene feels more like a showreel for HBO’s VFX team than for you.

Let’s settle on a warm tone. This is for the first clip in your showreel, so you want something that grabs the viewer’s attention and gets them on side with you immediately. After tone, I like to throw out some descriptions. Give it a go and see what feels right:

- Bubbly

- Banter-ey (that’s a word, right?)

- Is it a comedy scene? Something a bit heightened?

- Informal, but with some tension?

- Is it maybe something in a cafe, bewteen two friends?

- Not a cafe, but two old friends

Coming up with Writing Ideas

Thinking about the tone of the piece might be enough to inspire you. As I was writing out my descriptions above, I started getting the shape of what this scene might be. But let’s say you’ve already got a serious piece in mind between two friends, or you don’t want to come across too quirky, so bubbly is out. That’s okay. It’s as important to nail down what you don’t want as it is what you do.

You may want to look elsewhere for ideas. Another thing I ask actor clients about is inspiration from existing media. Is there a particular show that you want the scene to be like? Perhaps there’s a show you don’t want it to resemble—the less like Friends the better, for example…

Just remember: you’ll waste away in front of a blank page before you come up with the perfect idea, so don’t torture yourself into thinking you have to. Here’s what I do. I try to pick a really simple, direct idea for a scene. Could be two characters waiting for their car to fill up with fuel. And I ask myself: how do I make this interesting?

If I’m stuck for inspiration, the other question I like to ask is how a writer or actor I admire would make it interesting. How would they turn it on its head, and make something seemingly boring into a scene I’ll remember for years to come?

Situation Isn’t Story

I like that idea about two characters waiting for their car to fill up with fuel. I reckon there’s something there, so let’s use that. If I were writing for you, this is when I’d go off and write a couple of drafts before showing you something. But since we’re in this together, you’re saddled with me for the time being.

An important thing to remember when writing a scene for your showreel is that a situation is not a story. The situation can be fascinating—you could be the first astronauts on a brand new planet—but if there’s no story we’re going to be bored as hell before you know it. Often, you come up with the situation first, so you need to find the story to push it along.

Where do we find story? In characters. Good story is all about characters wanting something (their objective) and fighting for that objective with every line/movement/moment they have (action). It’s exactly the same with acting, except this time you’re the one creating the drama by dictating the conflict. So develop two characters and ask yourselves what they want: the want has to be something they can achieve within the scene and involves the scene partner. For example:

- Character A (this will be your part) wants B to turn the car around and head home.

- Character B wants A to give their family a chance on this holiday, and not be worried about making a first impression.

Suddenly, from a situation and a few random character thoughts, a story is emerging!

Character A—that’s going to get old, let’s call them Hannah—is on a road trip with their partner Sam to meet Sam’s family. As their car guzzles fuel by the side of the road, Hannah is trying to convince Sam to turn back, fearing that she won’t be impressive enough to Sam’s family. Sam, seemingly spurred on by wanting Hannah to be more confident, is trying to push on.

Enough thinking and planning. Time for the first draft.

The First Draft

Your first draft will be terrible. Don’t worry, though, because they all are. That’s their function.

In your first draft, get every idea and thought down on the page. It will be over-written, overwrought, overly cloying and cutesy. Most alarmingly, at three pages, it will be overlong. But this is exactly why you draft. Once the idea is out on the page, you’re no longer creating but refining. The editing process is the most freeing tool of any aspiring writer, as you have the chance to trim the fat and make it better. Never show your first draft to anybody. It’s always for you and only you.

Once you’re at this stage, you’ll begin to find your own rhythm and writing process. I won’t bore you with my own, but I will advise you not to read back over your first draft until you’re done. (It’s easy enough for a one-and-a-half page script; less so for a full-length play.) The minute you start re-reading your draft, you’ll want to fix the mistakes you’ve already made. Push on, buoyed by the knowledge that you will come back. If you stop and tinker, you risk never reaching the end of the scene.

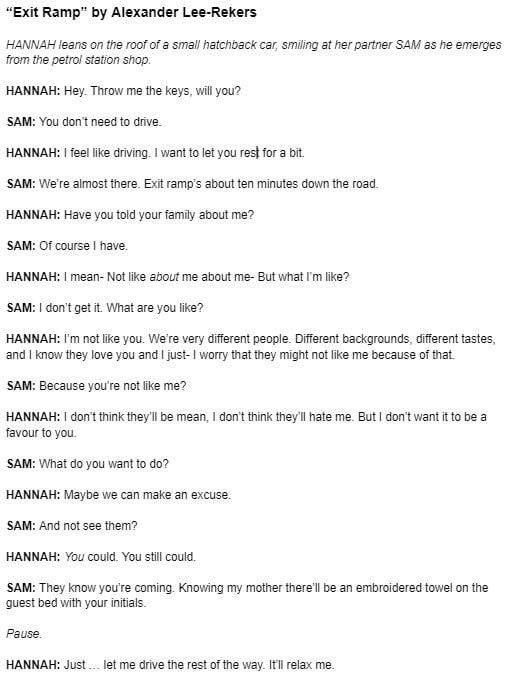

“Exit Ramp” First Draft

So here’s what I came up with. I’m breaking my own rule and sharing a first draft.

So. The characters are there. The story is there, informed by the situation. It’s not a bad first draft, but it’s still a first draft—which is to say too long and over-written.

What have we lost, though? The tone. Where’s the warmth?! What’s there to grab an audience and get them focused on your performance? And here’s something else to be aware of: note that while Hannah does fight for something in this piece, she’s not flexing a lot of power. Her status is quite low; it works within the context of the scene but doesn’t really showcase you, the actor who will play her, in the most exciting way.

On the page, it reads fine. And for a first draft, I’m fairly happy with it. But now’s the time to give it some oomph and direction.

Drafting and Cutting your Script

The first thing we want to do is start the script when it starts getting good. When does the action begin? When Hannah asks “Have you told your family about me?” That’s the drama, that’s where things get complicated. Why fumble around with keys and driving and all that malarkey? Whatever else we do, we’re going to lop off that first section and begin it there.

You might notice that the situation of the script is becoming less important all of a sudden. Don’t worry about this. The car filling up with fuel is still there in your mind, in the world of the story, but it’s secondary to the drama between these two characters. Don’t fret if your situation becomes secondary—or could be replaced entirely. As you’ll likely be filming this in a self-tape set-up and not actually filming it like a short, chances are you’ll just be relying on the characters to convey the world anyway.

Double-ups

One last thing to be aware of. I call these double-ups. Double-ups occur when a writer conveys the same idea or information to the audience twice. As a learning exercise (I swear) I have littered this first draft with them to give you some examples.

- “I feel like driving.” followed by “I want to let you rest for a bit.” Hannah wants to drive.

- “We’re almost there.” followed by “Exit ramp’s ten minutes down the road.” Trip’s nearly over.

- “I don’t get it.” followed by “What are you like?” Sam is confused about what Hannah is saying in regards to his family not liking her.

In each of these instances, I have conveyed the thought in bold twice, using the italicised sentences to say the same thing. You fix double-ups by becoming aware of them and cutting them. Once you do, you’ll be surprised how sophisticated your writing will seem: it’s less literal, more reliant on subtext. As an actor, you give yourself far more interesting choices to make in order to convey the underlying meaning of the scene!

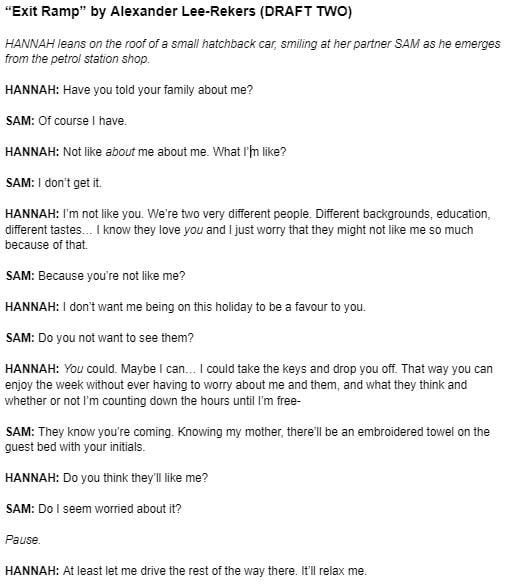

“Exit Ramp” Second Draft

So, our checklist for draft two is to find a warmer tone, cut the piece down and remove the double-ups. Let’s see what we end up with:

Already, this piece is better. Hannah seems more assertive in this version, partially because I got rid of all those punctuation marks that make her seem like she’s tripping over her thoughts and cutting herself off. I’ve also given her more to say (thanks to the later starting point and removing of double-ups) so she argues her case better. Now the choice she makes to drive at the end feels like a positive step, rather than her giving in. The tone of the piece feels a lot better as well. Sam and Hannah’s relationship seems a little less frosty, with him genuinely supporting her and speaking to her worries rather than shrugging it off with a comment about his mother’s embroiding skills.

Would a third draft of this piece be even better? Probably? A fourth? Possibly? A fifth? I mean, it’s one page. At some point you just need to put the pen down.

Filming your Original Showreel Scene

When it comes to actually filming your scene, treat it like any other piece you might select for your showreel. Take off your writer hat and approach it like an actor who has never seen this material before in their life. Do script analysis and character work to complexify the piece. Often, these are not apparent to you even if you wrote the material, so be ready to discover some subtext you may not have realised was there.

When it comes to shooting your own work, remember that it’s your team that will be most helpful. As they can bring an external (neutral) perspective, they’ll be the best resource you’ll have when it comes to noticing any mistakes or oversights—especially those pesky double-ups. I probably should have said this earlier, but if you’re going to be a writer and hand your work to actors. You must never be precious. Feedback may be confronting or even hurtful. But everybody wants the same thing.

Conclusion

Writing anything is hard. Writing for yourself can be a terrifying prospect, as it places even more responsibility in your hands to do a good job and try to not ruin your acting career in one sixty-second clip. But writing is such a wonderful skill for actors to develop, and working on how to write a scene for your showreel is a great example of just how useful it can be.

As a parting piece of advice, let me urge you to keep writing. Take on bigger and more exciting projects. Write a vehicle for yourself to perform, write a cabaret, write a short film, write a full length sci-fi epic screenplay. Then go out and make it! When you write, you put yourself in charge of a tiny world—and the fate of the characters and their destinies in your hands. It’s a tremendous responsibility for any artist. But there’s nothing quite like it…

Good luck!

Leave a Reply